A Dismal Winter Highlights Climate Risks in Lending

It hasn’t been a great winter here in Maine. Snowfall was practically non-existent other than in the mountains and even there barely so. Wind and rain wreaked havoc from November to February in all parts of the state including during a major storm in December and back-to-back storms in January. Temperatures were (once again) significantly above normal. Per Meteorologist Keith Carson, Bangor had its second warmest winter on record and Portland had its third. And if things were bleak here in New England, the situation has been even worse in the upper Midwest, where temperatures in February were a full 15+ degrees warmer than usual according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration:

It would be easy to roll an eye at all of this and offer a sly chuckle that warmer temperatures in the wintertime are actually not that bad especially when you live in a cold, dark place. And really, who among us living here in the Pine Tree State didn’t leave for lunch on some random day in February when the sun was shining and temperatures were up and think, “Well, this is kind of nice actually.”

Of course, the risks from climate change are so significant that it would beyond the scope of a single article to count them. Just here in Maine, if ocean temperatures continue to rise (and they are rising in the Gulf of Maine faster than anyplace in the world), it puts entire industries at risk. The lobster will move north to colder Canadian seas, for example. Rising tides and bigger storms are already putting shoreline real estate in major peril, not to mention municipal and state infrastructure, much of which ended up completely underwater from January’s storms. More inland, rising temperatures are already impacting the ecosystem, affecting many of Maine’s heritage activities from hunting and fishing to skiing and snowmobiling. Farm harvesting cycles from maple syrup in the spring to berries in the summer to potatoes and broccoli in the fall are all being disrupted. And speaking at least for myself, if the tradeoff to not shoveling as much snow in January is more ticks and mosquitos in June, that is not a bargain I wish to make.

For today, though, I wanted to talk from the bank perspective. Banks are in the business of both investing in risk and managing risk. As long as banks have been lending money, there have been risks related to weather and the environment. This is nothing new. What is different in recent years, however, is the frequency and severity of costly weather-related events. This may be a slight exaggeration, but the general consensus here in Maine is that we have experienced at least three hundred-year storms in the last 12 months. That is a major risk to businesses, borrowers, and, therefore, banks. Damaged property, loss of business activity, more expensive insurance premiums: you name it, we have seen it as a result of weather-related risks.

Good banks with sound lending practices are already mindful of climate risk on their own. How could they not be? But the OCC and other bank oversight organizations are also cracking down. This past October, regulators issued guidance requiring banks with assets over $100 billion to factor climate into their banking practices and lending decisions. All told, these new rules affect about 30 banks including all of the usuals like JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citi, and the rest all the way down to Santander Bank and Flagstar Bank with assets of just over $100 billion each.

The guidance reads:

Financial institutions are likely to be affected by both the physical risks and transition risks associated with climate change (collectively, climate-related financial risks). Weaknesses in how financial institutions identify, measure, monitor, and control climate-related financial risks could adversely affect financial institutions' safety and soundness…

…the principles provide that financial institutions' management should employ comprehensive processes for identifying climate-related financial risks consistent with methods used to identify other types of emerging and material risks. The agencies made changes to the draft principles to clarify that management should incorporate climate-related financial risks into their risk management frameworks where those risks are material.

Among the specifics, bank boards of directors and management teams will need to implement monitoring plans of climate-related risks as well as come up with ways to quantify risks. For all the proposed new implementation, however, there is some softer language as well, including an acknowledgement that this is an evolving process and all lending decisions still rest with the bank itself. The new rules also do not prohibit lending to businesses that could be perceives as anti-climate, such as those in the oil and gas industry. But the purpose is clear: banks need to start thinking about climate risk and factor that into lending decisions if they are not already.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell endorsed the measures, saying:

The Federal Reserve has narrow, but important, responsibilities regarding climate-related financial risks, which are tightly linked to our responsibilities for bank supervision. Banks need to understand, and appropriately manage, their material risks, including the financial risks of climate change. The guidance issued today is squarely focused on prudent and appropriate risk management. I am therefore able to support its issuance.

These newly established climate principals are pretty broad at this point. It is not clear what an adequate “risk management strategy” might be or what penalties there could be for non-compliance. But it is clear that climate is now on the radar of the banking regulators (at least as it pertains to large banks) and that these new requirements dictate board and management teams must anticipate and respond to climate-related risks.

What about the smaller banks?

For now, the climate guidance only applies to those larger banks. And smaller community banks are wary and are already defensive. The Independent Community Bankers of America (ICBA), which is the lobbying organization for smaller banks, came out aggressively against the new measures, saying:

With decades of experience managing concentration risks, maintaining strong underwriting and insurance practices, and responding to natural disasters, community banks are seasoned experts at monitoring the risk of their lending and investment portfolios, and knowing when and how to reduce their loan concentrations. As stewards of their local communities, community banks have prepared for, responded to, and survived myriad natural disasters since the early 19th century, and are best positioned to evaluate the risk of their geographically limited loan portfolios.

For this reason, ICBA is strongly concerned by the increasing focus of the Biden administration, lawmakers, and state and federal bank regulators on the topic of climate change. Banks are being pressured to address loosely defined or studied climate-related financial risks.

The ICBA’s conclusion about the new climate guidance as it could potentially pertain to smaller banks in the future? They say:

ICBA will oppose any federal or state climate risk regulation that adversely impacts community banks and their ability to support their communities and customers.

The bulk of this opposition is really in the fact that smaller banks do not want additional limits on their practices and burdens on their activities from new oversight and reporting requirements; even bank leaders who have real concerns about climate change and the risks to their banks could be opposed to the new rules simply from not wanting another set of regulations to be mindful of. Their argument is that larger banks have more built-out teams and processes for responding to federal requirements and stipulations, whereas smaller banks, which are typically located closer to their customers and whose lenders and credit analysts have a better handle on their activities and risks, are already mitigating risk through current procedures and protocols. We know what we’re doing, leave us alone, is probably the best way to summarize the smaller bank sentiment.

It seems certain that proponents of the new climate guidance would like to expand the framework to smaller banks in the future and perhaps enact some more firm consequences for non-compliance; although the rollout this past October was broad in nature and only applicable to larger banks, the intent is surely to soften the landscape for more comprehensive applicability in the future. So bank management teams should stay tuned. Of course, with the fickleness and pendulum swings of politics, all of this new guidance could be dampened or outright reversed depending on the results of the upcoming presidential election. What is unlikely to be reversed as easily, however, is the fact that most of the ten warmest years since 1850 have, in fact, been in the last ten years, and temperatures in 2023 were a full 2 degrees above the 20th century average. Risks from climate are certainly not going away anytime soon, which means the risks to borrowers and banks are not either.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

Weekly Round-Up

Following up on an article I wrote a few weeks ago about the National Association of Realtors (NAR) getting hit with lawsuits that could change the compensation structure for real estate agents, news broke on Friday that the NAR has agreed to a $418 million settlement and will change the standard 5-6% commission model - big news worth monitoring in the coming weeks if you’re in the real estate industry as an agent or otherwise. Purchasing costs are likely to go down, which is good news for beleaguered would-be buyers. Read more here via The Hill.

Cars are getting stuffed with technology. One result? Driving data is ending up in the hands of insurance carriers (sometimes without the driver’s knowledge), which are then raising premiums on bad drivers. Mixed feelings on this one! Bad drivers should pay more for insurance, but the data being sold without consent feels icky. Read the original reporting from the New York Times here or the non-paywalled overview from Morning Brew here.

Speaking of The New York Times, I listened to a fascinating podcast episode this week of The Daily about a shadowy group of billionaires who have been buying up land outside of Silicon Valley to potentially build a new city. I didn’t think it was going to be as interesting as it was, but I found the story (and the podcast episode) fascinating. Listen to it here.

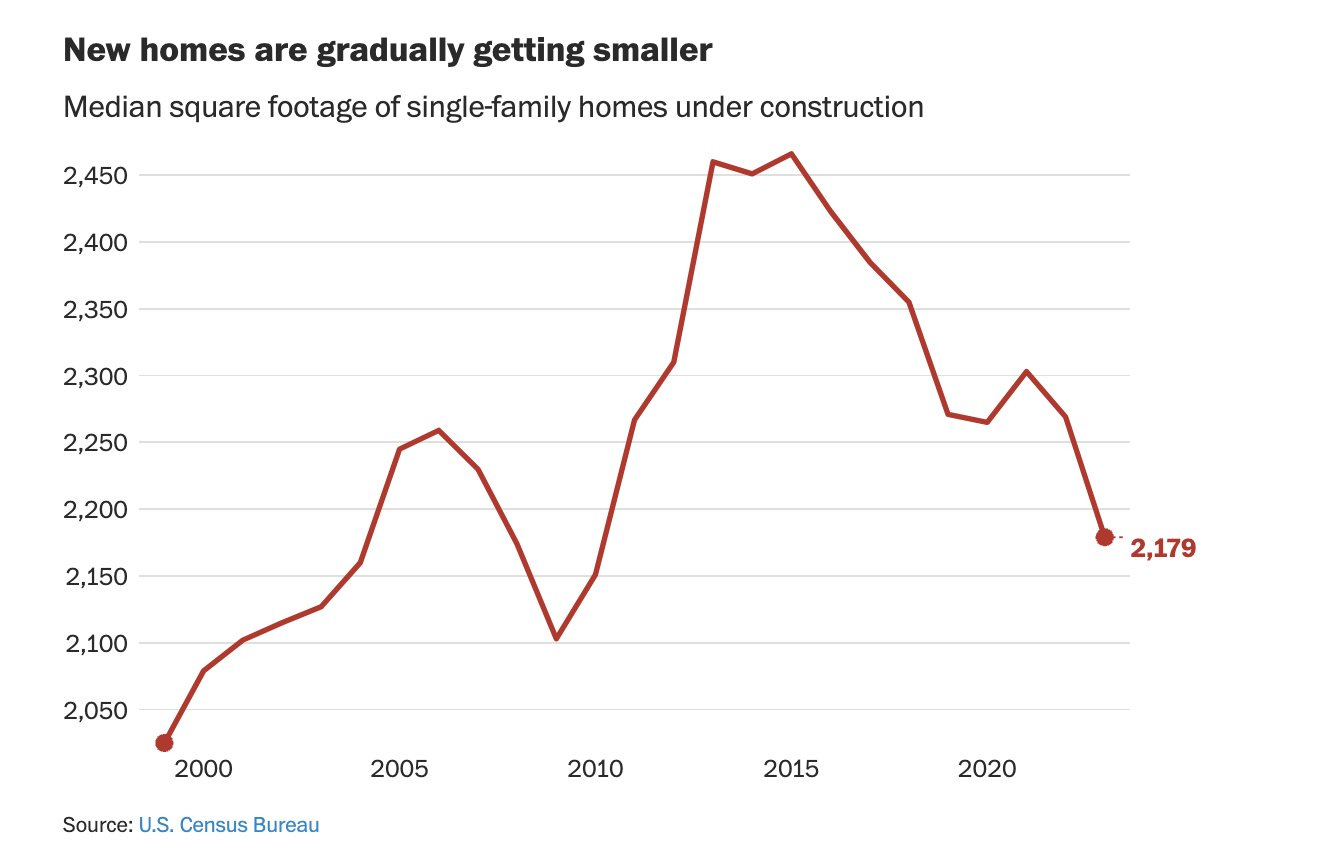

Homes are shrinking! In the past ten years, the average single-family home under construction has shrunk by about 300 square feet. The high cost of construction (including materials) and perhaps smaller families and more people living alone are likely all among the reasons why. The article is paywalled, but you can read more via Abha Bhattarai in The Washington Post here. The chart below is from the article:

One Good Long Read

From Rachel Levin in Outside Magazine, a story from 2021 about the migration of workers out of San Francisco and Silicon Valley to places like Lake Tahoe and Truckee: “When the Techies Took Over Tahoe.” This story features the creation of a “non-welcoming committee” and the line, “One old-timer plastered his truck with a banner that read ‘Go Away’ and drove around and around a traffic circle.” This was an entertaining story and a look at what I call “fresh nostalgia,” which is an interesting look back at something that was not even that long ago in the great scheme of things. Plus there is some good talk in here of what a heated real estate market looks like. You can read it here.

Have a great week, everybody!