Greetings! Welcome to The Sunday Morning Post. A hearty thank you to everyone who reads these articles each week and a word of welcome to all of the recent new subscribers. If you were forwarded this email or happened upon it another way and would like to receive my articles in your inbox each Sunday morning, just click Subscribe below.

“Buy low, sell high” is the oldest investment axiom in the book. I would submit that the borrowing version of this is “Fix low, float high.” With that in mind, if you are seeking financing anytime in the next 6-12 months, my advice is to sacrifice the clarity and stability that come with a fixed rate and instead talk to your banker or loan officer about going variable (i.e. floating). Why? Let’s dig in.

Anti-Variable

Most Americans might be surprised to know that in many other countries home loans mostly carry variable interest rates. In the United Kingdom, for example, most home loans have a fixed rate period of only two or five years and then become variable. This has caused a great deal of economic angst over the pond in the past year as interest rates in Great Britain as in others parts of the world have skyrocketed. As the variable component of most Brits’ home loans has kicked in, their payments have jumped significantly.

Americans are understandably skeptical about variable rates for the obvious reasons. No one wants to risk having to pay more on a monthly basis and people like the predictability of knowing what their monthly payment will be for the life of the loan. With a long-term fixed rate, a home can also act as an inflation hedge, at least when rates are low. Burnt into our collective economic conscience is also the notion that variable rates were a key part of the 2008 Financial Crash; as people’s initial fixed-rate periods expired and their loans went variable, their payments increased significantly and many homeowners could no longer afford them, which made them default on their mortgages. The crumbling of the mortgage market then spread through the entire economy through a contagion effect. In reality, of course, the catalysts for the Great Recession were much more complicated than this, but one of the general conclusions from the time period was, “Fixed rates = good. Variable rates = bad.”

The vast majority of home mortgages in this country are, indeed, fixed. This is due to consumer preference, a different banking system than in places like Great Britain, and for the simple math of it all: fixed rates have just been more advantageous to homeowners for most of the last decade. According to Experian, in 2020, 97% of new home mortgages were fixed rate, which makes sense since long-term fixed rates were so low.

As rates have increased since 2020, the portion of new mortgages that are variable has also increased. Real estate research institute Black Knight has calculated that the percentage of mortgages that were variable rate peaked at 12% in October 2022 and was around 8% this past spring. I have not seen data for more recent months, but I would guess the portion of variable rate mortgages today is at least 10-12% if not higher. In fact according to Mortgage News Daily, the average 30-year fixed rate this week was 7.56% and the average 5/1 ARM variable rate was 7.21%, so a variable rate does offer some savings at the current time plus the change for downside movement in the months to come (more on that below).

On the commercial side of things, most commercial loans are fixed for either three or five years and then become variable, which presents a lot of risk to commerical borrowers in the current environment who may have fixed at, say, 4.00-5.00% a few years ago, but might be poised to go variable or re-fix at a much higher rate. This is definitely something for commercial borrowers to be mindful of in the months ahead.

The Future of Rates

The main reason why a variable rate loan now makes sense versus a fixed rate is that over the next 24-36 months there is more downside likelihood in rates than upside. Sure, the most obvious risk of a variable rate is that rates can in theory rise indefinitely. People probably do not need a reminder that the 30-year fixed rate mortgage topped out around 19% in the early 1980s, which would still be a pretty sizable jump from where it is today. But are mortgage rates going to 19%? Almost certainly not.

I wrote in July about when I expect interest rates to start to decline. My conclusion then was that rates would start to drop in March 2024 as inflation continues to slow and then would decline steadily for the rest of 2024 and into 2025. The rate environment has been pretty unstable since then, so it’s worth another look at that prediction to see if it still holds up.

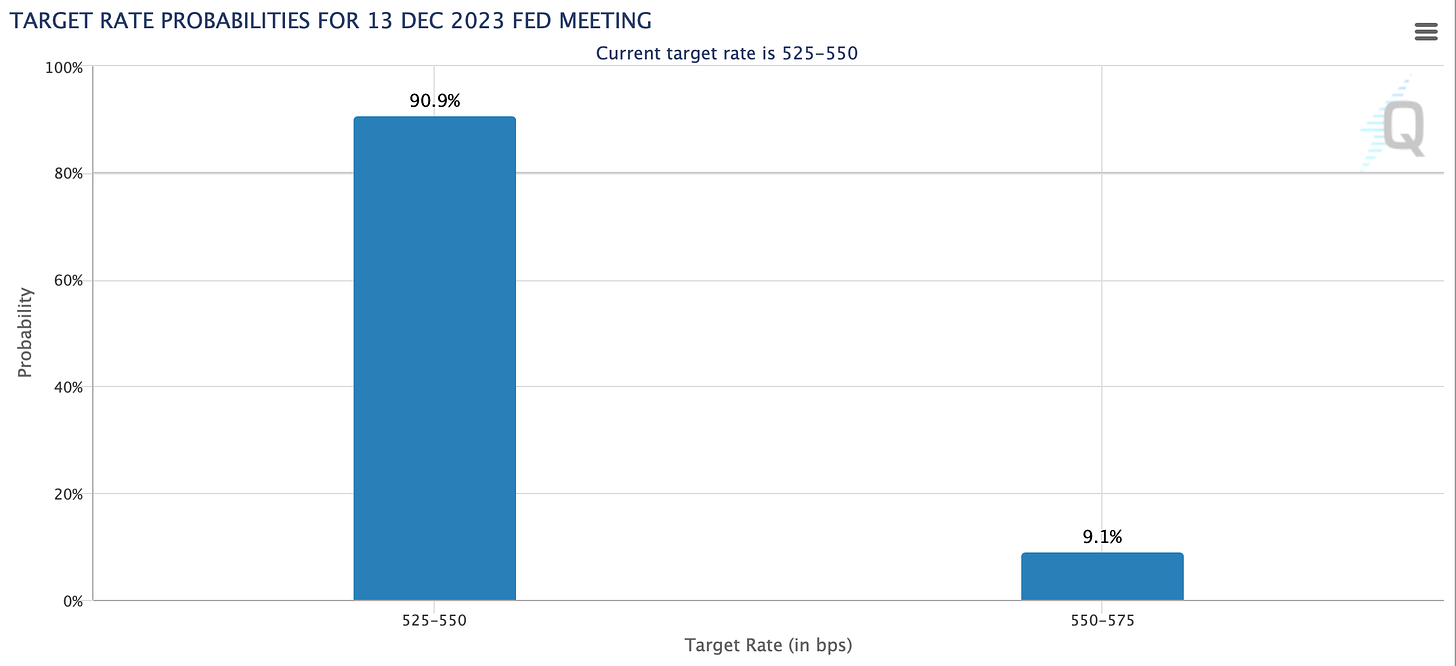

One research source I use to track future rate likelihoods is the CME FedWatch Tool, which aggregates data from economists and others and parses the public statements of various Fed officials for keys as to future rate movements. Currently the Federal Funds target range is 5.25-5.50%. The CME FedWatch Tool gives a 90.9% likelihood that this will hold through until the end of the year with an 9.1% change the range will bump up to 5.50-5.75%. In other words, it is likely that rates are going to stay more or less where they are through the end of the year, at least according to these probabilities.

But what is more critical to borrowers is the intermediate to long-term outlook. Banks typically price loans on both the residential and commercial side around what the Fed is doing, so what borrowers need to understand is what rates will be like 6, 12, and 24 months from now and beyond (to the extent possible; the longer time horizon you are looking at the less certain these predictions become because of all the other variables that crop up over time in the economy, politics, and things like wars and geopolitics around the world).

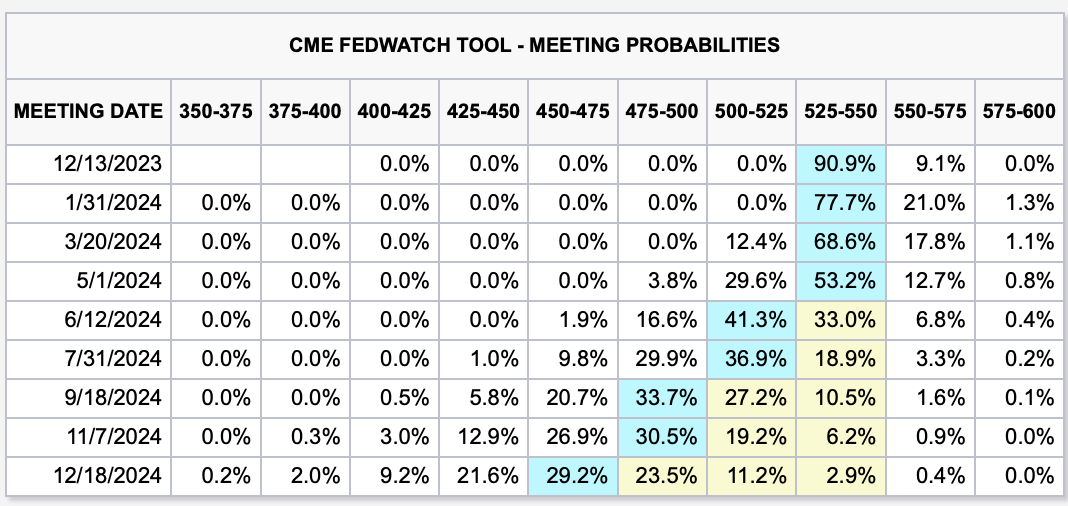

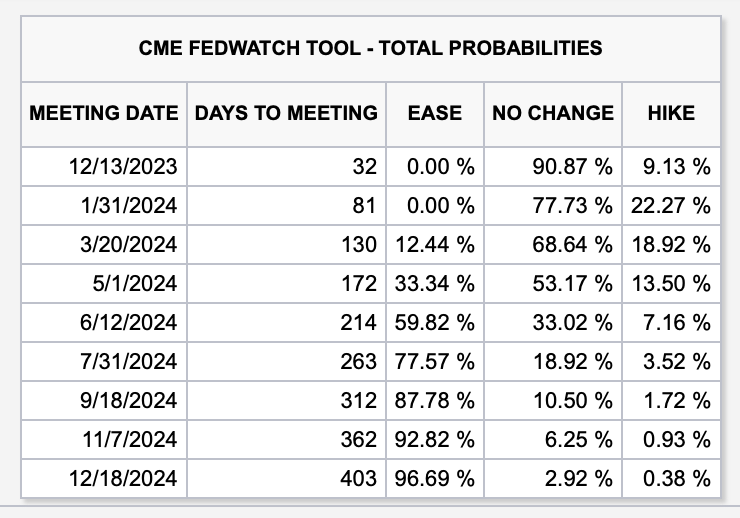

As you can see from the tables below, also via the CME FedWatch Tool website, predictions for when interest rates will start to decline show that the first month with a greater likelihood of rate drops than of rate staying where they are now is June 2024.

Of note, there is almost near universal agreement that by the time we get to next November, rates will be lower than where they are today with a 92.82% likelihood of a decline in rates, a 6.25% likelihood they will be where they are now, and a slim 0.93% chance they will be higher.

All usual disclaimers should apply here about how this article is meant to be educational and not a specific form of financial advice. Everyone’s circumstances are different. And there are a lot of things that can happen that might could skew the likelihoods above. If inflation rips back higher, for example, the Fed could still hike rates again. And likelihoods are just that: chances and probabilities. Although a 0.93% chance is pretty slim, it is not nothing.

So what should borrowers do? To the extent possible, a variable rate makes sense at this point. You may start your loan with an interest rate that is a little bit higher than it would be on a fixed rate, but by this time next year you will probably be better off. You will also benefit with each subsequent rate drop. There is definitely a scenario where rates drop quarterly or at least every six months for several years in a row. With a variable rate, there is no need for a refinancing or a loan modification; the rate on the loan would simply drop in accordance with the terms of the variable rate. At the very least, it is worth a conversation with your lender to discuss.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

Weekly Round-Up

Here are a few things that caught my eye this week:

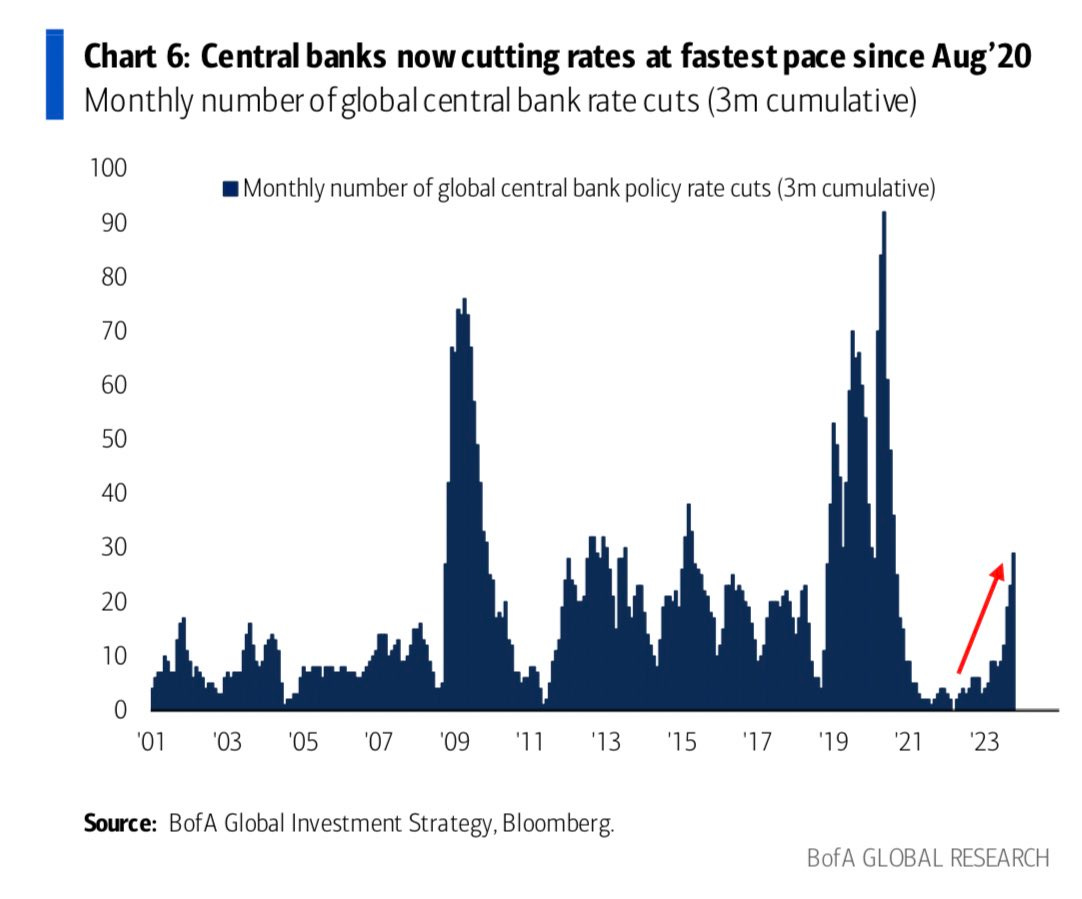

Per Bank of America, central banks around the world are, in fact, starting to cut interest rates. Not here in the United States quite yet, but the cuts are coming. The chart below shows there were 30 interest rate cuts around the world this past month.

WeWork recently filed for bankruptcy. There is an interesting Wall Street Journal podcast that tells the story, but also notes the company hopes to live on and that one of the incentives to declare bankruptcy was so the company could break its leases. That is now exactly what is happening with WeWork backing out of 70 commercial leases including 35 in New York City. Read more here via Fortune (sorry, the bulk of the article is behind a paywall).

Joseph Politano, who writes the Apircitas blog on Substack, has a detailed article this week on how wages have been rising the most substantially at the low end of the wage spectrum, although these workers are also the most likely to be the most impacted by inflation. Read more here.

Have a great week, everybody!

Great analysis. It will help borrowers to make up their mind. The fly in the ointment may be the need to attract buyers for US Govt debt that puts a floor under the market. Thats a dynamic that may not be catered for in the Fedwatch tools. Or is it? If private sector earnings decline and the savings pool is used up, and unemployment increases, Government receipts will decline. If, in an election year, the Democrats opt for more spending, with an increase in the deficit? What then?