Inflation Lurks

Markets, borrowers, and banks hone in on the Fed's use of the word "transitory"

Welcome to The Sunday Morning Post newsletter! Each week I write an article about economics or personal finance meant to educate, inform, and entertain. Subscribing is free and you won’t see any ads or have your email address shared or used for anything other than the delivery of researched, readable content that is jargon-free and informative. You’ll also get a list of the links and other new stories that have caught my eye. Click below to subscribe and thanks for reading!

Inflation Lurks

The U.S. Department of Labor reported on Thursday that consumer prices increased by 5.0% on a year-over-year basis in May, the highest jump since 2008. This was after a similarly large increase of 4.2% in April. Fed officials say the hot inflation numbers are “transitory” and that prices will settle out as the economy continues to recover from the COVID-induced recession. This opinion is supported by many economists and financial commentators, but it is also a gamble that could have vast implications for the U.S. economy over the next few years and beyond if inflation does continue to heat up. So what’s going on? Let’s dig in.

The Arguments Against Inflation

There are a number of fair reasons why the most recent jumps in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) should not raise many eyebrows let alone raise alarm. First, CPI figures on a month-to-month basis compare the price of a basket of goods with the same prices from one year ago. The base of comparison for May 2021, in other words, is May 2020, and as everyone knows the economy was not exactly firing on all cylinders in May 2020 amid the early days of shutdowns and quarantines. Of course prices are going to be up in 2021 versus the same point in 2020.

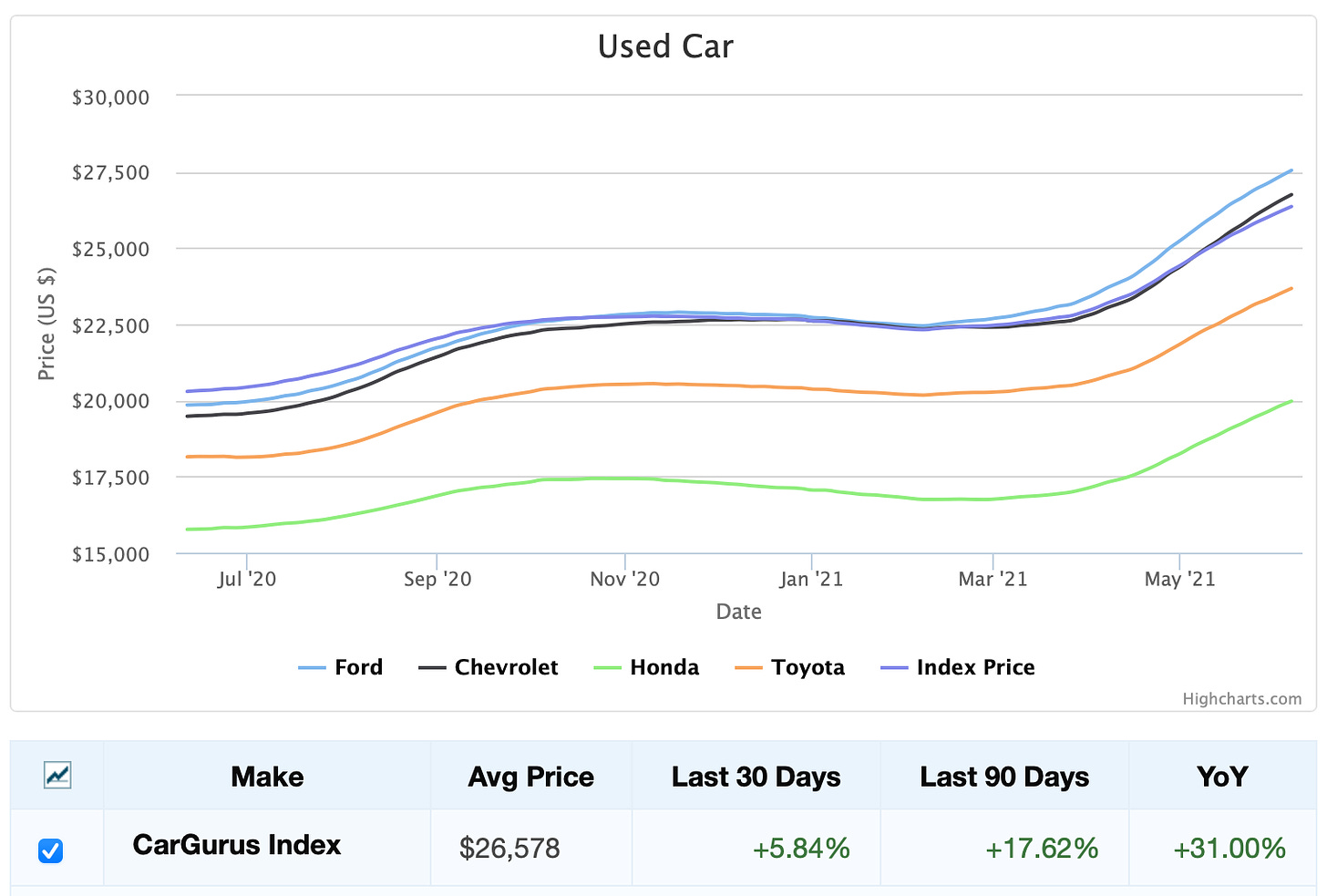

Second, there are a lot of quirky things happening in the economy right now. Prices for certain products and in specific industries are especially skewed. Used car prices, for example, are up 30%+ in the last year.

Airfare, hotel rooms, rental cars, and other travel-related expenses have also surged as an increasingly vaccinated nation has the tourism market roaring from Maine to Florida to Hawaii.

I spoke to a friend who works on Wall Street this week who is not at liberty to be quoted publicly but who offered a helpful perspective nonetheless. The friend pointed to the impact on CPI figures of certain goods and services like the ones noted above but also to the fact that there are significant COVID-related supply chain issues right now that are pushing prices up amid strong demand. These supply chain issues will eventually settle out. He also raised the point that there are long-term deflationary factors at play, including the forces of technology and globalization, both of which have a tendency to bring prices down. Lastly, he noted that bond yields barely budged on Thursday following the hot inflation report, and in fact went somewhat in the opposite direction that you would expect if a spike in inflation were imminent.

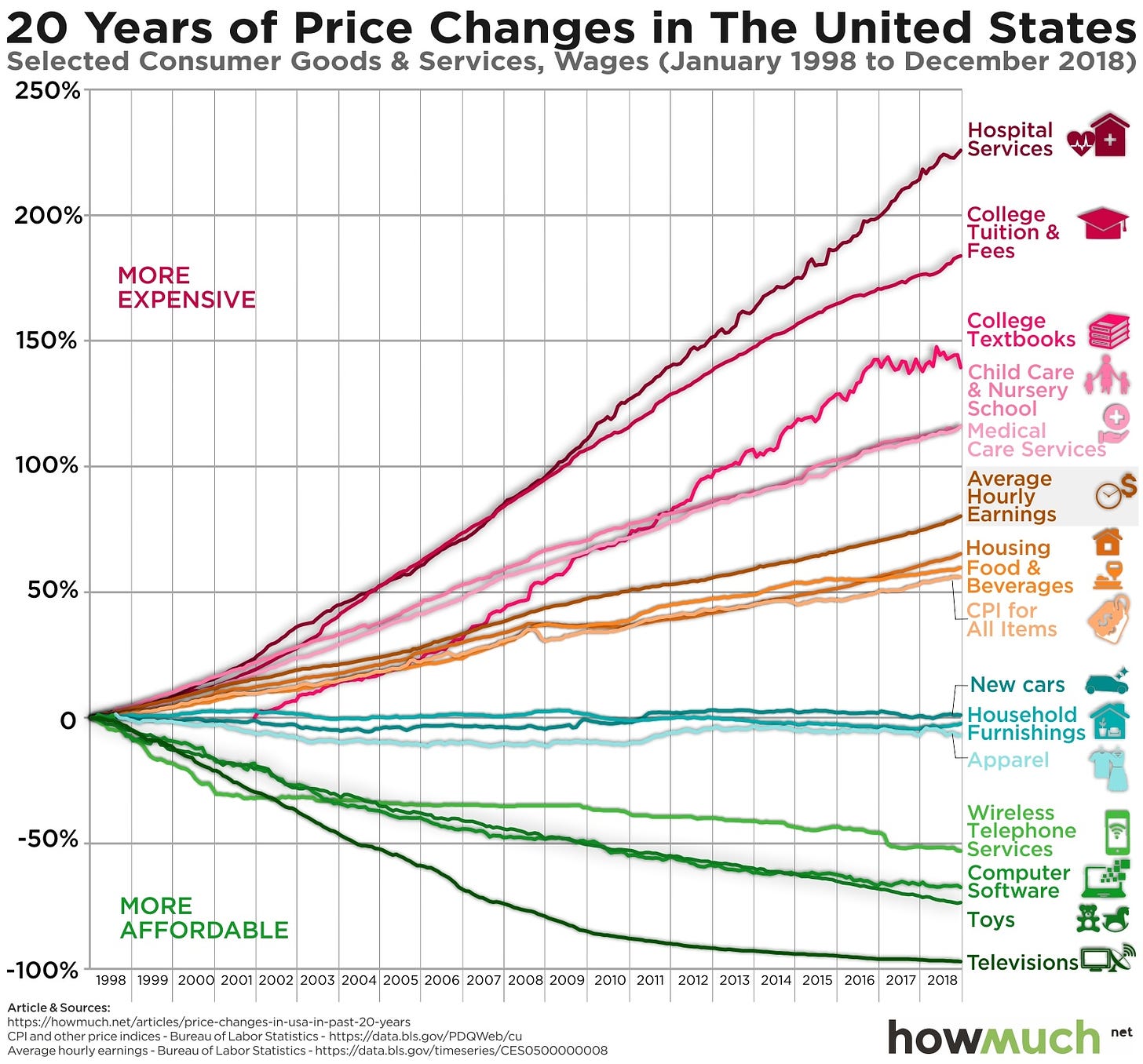

On the point about technology driving prices down, consider the chart below showing how prices have changed for various services and products over the last 20+ years. You can buy a lot of TV, for example, for a pretty small amount of money as compared to, say, twenty years ago, which is reflective of both improvements in technology that have boosted quality of certain products, and globalization, which tends to result in cheaper prices for consumer goods even as quality improves:

As an aside, it’s perhaps no surprise to people that medical expenses, college tuition, and childcare are among the most inflated goods and services over the last 20+ years, which neither economic market forces nor government policies have been able to much dampen.

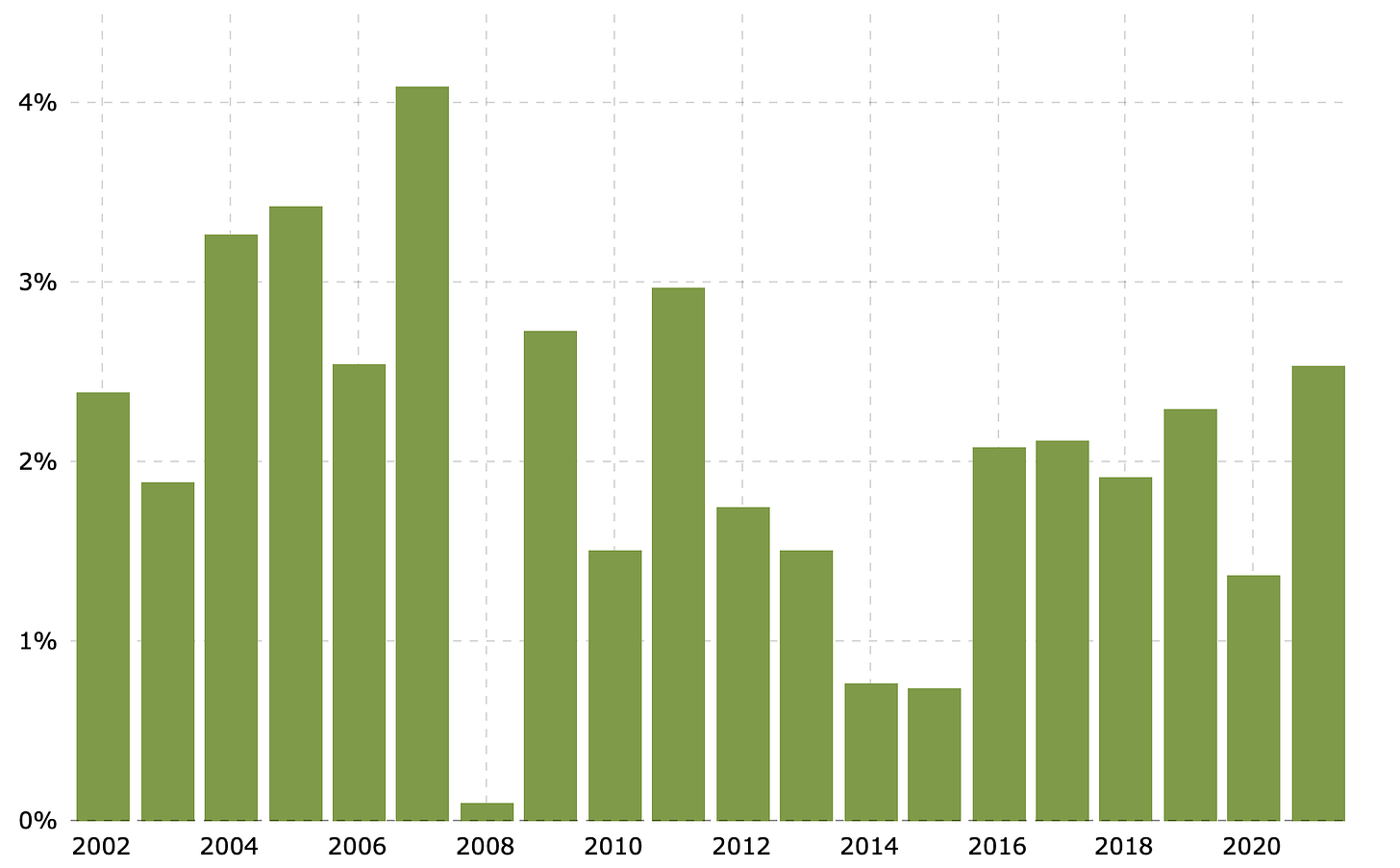

A final argument one could pose to suggest that inflation is not actually something to be concerned about is simply that many economists, academics, and other commentators have been predicting economic doom and gloom due to inflation for years and, well, it just hasn’t happened. Over the last twenty years, annual inflation has topped 3.00% just three times, all prior to the 2008 global financial crisis, and peaked above 4.00% just once, which was in 2007. For the past decade, annual inflation rates have been more or less averaging right around the Fed’s stated goal of 2.00% or just below:

Why Inflation Matters

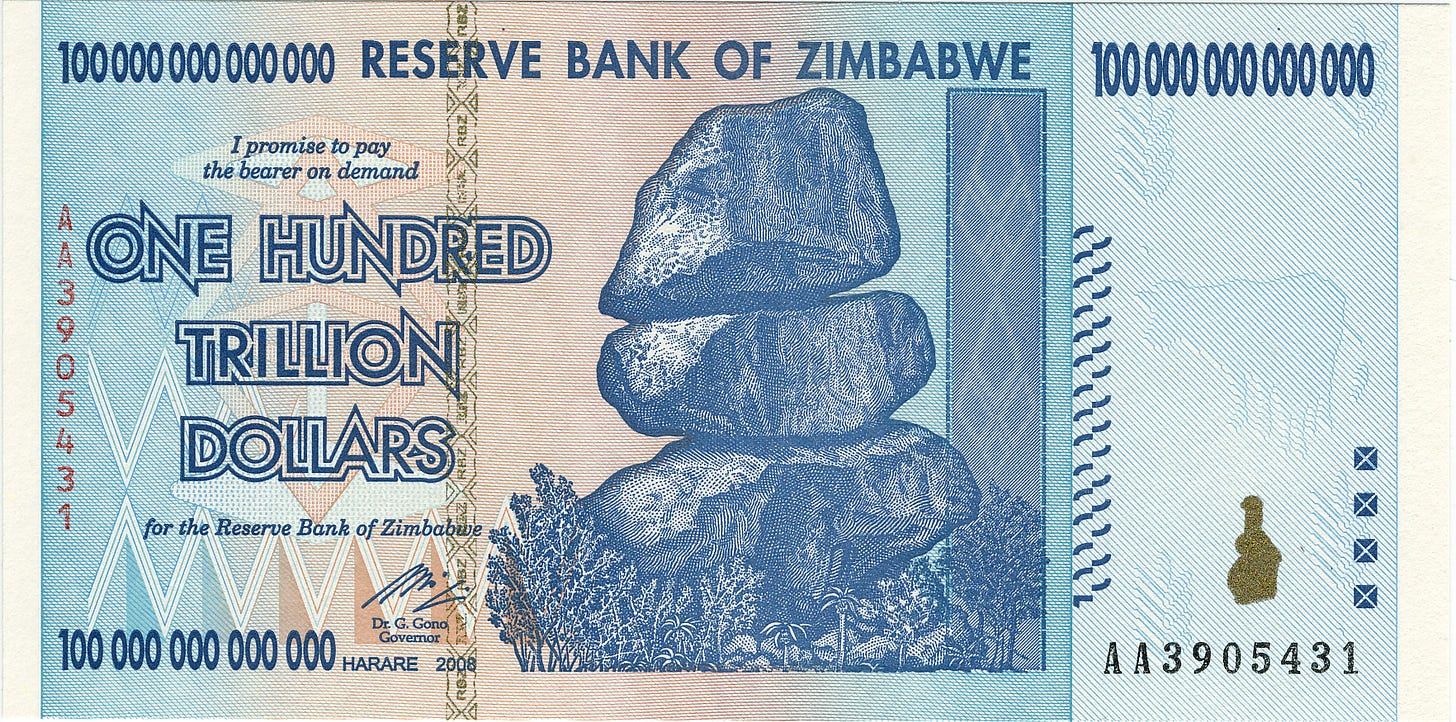

Inflation above a certain level is generally bad because it erodes the purchasing power of people’s wages and savings. When inflation gets really out of control it is called hyperinflation and it can ruin entire economies. Images of peasants bringing wheelbarrows full of German Marks to the market come to mind (one loaf of bread cost 200 billion Marks in Germany in 1923) or the image below that represents more recent hyperinflation in Zimbabwe in the late 2000’s (yes, this is a picture of a real bank note):

Suffice it is to say, policymakers, pundits, and politicians all generally agree that inflation above a certain level is generally bad especially when it gets out of control. The Fed is tasked with keeping inflation at or near its stated goal of 2.00%, although curiously enough the Fed is also tasked with promoting employment and as I discussed in last week’s newsletter, this can sometimes create a tricky balance with difficult and intriguing policy choices.

It should also be noted that certain types of inflation can actually be good. Or, to put it a different way, sometimes inflation that is bad to one person, group, or industry is positive for another. Consider wage inflation, for example, of which there is much of right now. To the business owner who has had to increase wages from $12/hour to $17/hour to attract workers, this increase in labor costs is generally bad at least from an economics perspective in that rising labor costs eat into the business owner’s profits (note: some business owners undoubtedly have altruistic or reputational benefits from paying workers more, but from an Economics 101 perspective, rising labor costs for the business owner are generally bad for that business owner). But for the worker, that $5 bump up per hour might be a life-changing amount of money and could lead to all kinds of positive outcomes. In a different example, if the price of corn doubles in a matter of months, that is bad news for the restaurant that has to buy corn by the ton, but it is good for the farmer selling it. Suffice it is to say that not all inflation is bad to all people at all times, but economy-wide inflation above a certain level is generally not good.

So What’s Happening Now?

Plenty of smart people say that the recent uptick in consumer prices is not really something to be concerned about for the reasons noted above. This is the position of Fed itself, which has said it believes higher prices are “transitory” and will settle into normal levels in the months ahead as the economy continues to emerge and stabilize from the COVID-recession.

From my perspective, I see a lot of inflationary pressures. Most notably, the economy is, in fact, roaring back. Thanks to a shallower dip due to COVID than perhaps was initially feared, significant government stimulus and COVID-relief payments to both individuals and businesses, and even further COVID-relief in the form of grants and other payments to hospitals, healthcare systems, states, and municipalities, there is a lot of new money flowing through the economy. The Fed has doubled its balance sheet since March 2020 and household finances are strengthening thanks in large part to stimulus payments, which, of course, was the entire point. Demand for goods and services is robust and prices are rising because of it.

I also am observing significant wage inflation. I want to underscore something I said above, that wage inflation from a certain perspective is an economic burden, but from the perspective of a low to middle-wage worker, a boost in pay can be a life-changing event, but wage compression upward through the employer pay scales compounds this impact. After all, once the person with six years of experience who was making $20/hour sees that the new hire is making $17/hour and got a $1,000 sign-on bonus, the person with six years of experience is going to expect a raise.

Interest rates have also been held low for several years now after a nearly 40-year period of (more or less) decline. In my work as a commercial lender, I am now observing that businesses are leveraging up by borrowing at these historically low levels. Business owners are taking their loan proceeds and investing in their companies, which should lead to new business activity and economic growth. After all, this is the Fed’s primary motive to keep interest rates low: to spur economic activity.

But there is a risk of overheating in all this. Significant government stimulus + a snapback economy + rising wages + leveraging up of corporate debt feels to me like a formula for inflation.

So What?

The Fed has stated that they aim to keep interest rates low until 2023, but my prediction is that they will start to hike interest rates sooner as the economy continues to recover faster than previously expected.

Are we at a risk of 1920s German or 2000s Zimbabwean hyperinflation? No, of course not. But is there a risk that monthly CPI numbers continue to show a steady and stubborn rise in prices for consumer goods and services? I think so. By the way, not only were April and May CPI increases fairly robust at 4.2% and 5.0%, but they also outpaced economists’ projections on the high side. In other words, not only was inflation high, but it was also higher than expected. This suggests to me a bit of groupthink when it comes to perceptions and expectations of inflation.

Of note, Deutsche Bank came out last week and became the most prominent voice yet to raise alarm bells about inflation, calling it a global “time bomb,” and that inflation could “create a significant recession and set off a chain of financial distress around the world, particularly in emerging markets.”

If inflation does continue to heat up, one of the mechanisms that the Fed will use to keep it under control is to raise interest rates. This increases the costs of borrowing for both businesses and individuals (and couples, families, etc.), and slows economic activity. The Fed did this most famously in the early 1980s when inflation was rising at a rapid pace; so too, in turn, did interest rates, including the rate on a 30-year fixed mortgage, which peaked at over 18%! The hikes in interest rates were enough to cause a recession, which was actually the Fed’s intent in order to keep inflation from further spiraling up out of control and doing even greater damage to the country.

There is a risk to businesses and individuals who are leveraging up right now, especially in commercial loans that typically only carry a fixed rate for the first three to five years before re-fixing at new rates or becoming variable: the cost of that borrowing may increase over time if interest rates rise. When projecting cash flows, business owners, investors, and individuals should calculate their numbers based on current interest rates, but they should also make calculations based on an upward shock of interest rates of 2-4% over the next few years. A project might work at an interest rate of 4.50%, for example, but does it work at 7.50%? It’s an important question to consider.

At the same time, banks need to underwrite and approve customers not only based on current interest rates, but also based on expectations of future rates. Risks abound as interest rates go up, so banks must factor in the possibility (and I say, in fact, the likelihood) of rising interest rates in order to guard against customers becoming over-leveraged. A combination of higher interest rates plus an eventual economic recession would put many borrowers in peril.

That being said, my Wall Street friend had an additional point to add, which may be at the heart of the Fed’s motivation to keep rates low for as long as possible: it is easier to put the reins on an overheated economy than it is to kickstart a cold one. And one year ago if you had said that the Fed’s biggest problem was the risk that the economy was going to strengthen too fast so as to cause inflation, I think that is something policymakers at the time would have been extremely grateful for.

CPI inflation reports are released on a monthly basis. Investors, borrowers, bankers, and anyone with an interest in the health of the economy, which is, of course, all of us, should keep an eye on them. For now, the bridge from today to 2023 is being built on the Fed’s use of the word “transitory,” which will undoubtedly be a much-debated and closely watched term in the months ahead.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com. Follow Ben on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram and subscribe to this weekly newsletter by clicking below.

Weekly Round-Up

Here are a few things that caught my eye this week and some further notes about today’s topic:

Conor Sen analyzes inflation in the context of the housing market, which may provide an indication that consumers and developers will back off of projects in the face of higher prices, a suggestion that inflation is, indeed, transitory. He says:

While prices may have risen faster and higher than most participants expected, now the market is starting to behave like this has been a temporary imbalance rather than a structural shift in behavior. Not only are some builders choosing to slow down despite historically low housing inventories, but sawmill companies aren’t in a hurry to expand capacity, choosing to rake in what they see as short-term windfall profits rather than invest for future demand that they’re not sure will materialize.

Jason Furman, Ec 10 professor at Harvard, shares some thoughts on inflation in a Twitter thread:

Vox has a pretty comprehensive explainer on inflation: https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/22346376/inflation-rate-explained-federal-reserve

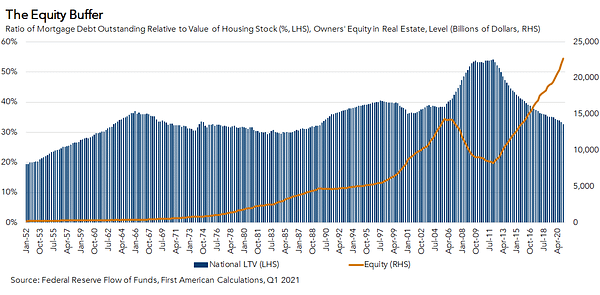

Odeta Kushi observes that U.S. homeowners have more equity in their homes than at any point in the last 30+ years:

A North Carolina high school principal says goodbye to his students in an especially sweet way:

Oh, and by the way, lumber futures continue to drop:

A Final Word

I am proud to have been recently voted onto the board of the Maine Community Foundation. The Maine Community Foundation distributed over $50 million in grants and scholarships last year and is at the forefront of some of our most important issues including broadband expansion and climate change. I look forward to being a part of this work.

My wife and I had a Letter to the Editor in the Bangor Daily News thanking the Bangor School Department for their incredible work to maintain in-person five-day-a-week school for kids all year long. We are so fortunate and we honor and thank the teachers, staff, and administrators. Click here to read the full letter.

If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, please consider sharing on social media or forwarding the email to others to help spread the word.

Got news tips or story ideas? Email me at bsprague1@gmail.com.