Rental Vacancies Have Been Dropping for a Decade. Why?

Right now the rental market is very tight. Turnover among tenants is low and property owners report low vacancies, lengthy waitlists, and dozens of inquiries when a unit does become available. Rents are also rising, putting a squeeze on renters, the very same people who are also having trouble entering the homeowners market with very little inventory available especially at low and moderate price points, heavy competition among fellow buyers, and rising interest rates.

The chart below shows the vacancy rate among U.S. rental units over the past decade. The current rental vacancy rate is 5.8%, up modestly from 5.6% last quarter, but still near historically low levels:

You would need to go back to 1984 to see vacancy rates as low as we are seeing now. The tight inventory and low churn are challenging for people looking to move or prospective tenants including home sellers who might be interested in downsizing to a rental or moving to a different locale. There are just not enough places for people to live right now. And, in fact, according to Kriston Capps in Bloomberg, the vacancy rate in rental units with professional property managers is just 2.5%!

Why is the rental vacancy rate so low? And will it last? I see five key variables that I think offer some explanations:

1. Home Prices Are Expensive

This is probably the most obvious reason why the rental market is so tight: home prices are too expensive for many renters to be able to afford, which means they must continue to rent. Home prices rose nearly 19% in 2021. The median sale price of homes sold in the United States in Q1 of 2022 was an astonishing $428,700. Exactly ten years ago? The median price was $278,000 (adjusted for inflation this amount would be about $343,000). Today’s $428,700 median price is just beyond the means of tens of millions of Americans.

2. A Period of Underbuilding

I wrote last August about how homes cost a lot less fifty years ago even when adjusted for inflation and I wrote in October about how we are short about 3.8 million homes to effectively close the gap between demand and supply. There are two related points here. First, there is just not enough inventory of homes-for-sale in the low to moderate price range. There is no “Sears Catalogue Home” today, the equivalent of a home that would market for $70,000-$90,000 in today’s dollars. In most real estate markets, if you said you wanted to pay $100,000 for a home let alone less, they would laugh you out of the real estate office. In my own home market of Bangor, Maine, it seemed that only a few years ago you could buy a really solid family home for $160,000-$200,000 and sometimes even less. Now that same type of home is probably $100,000—$150,000 greater in price if not more and that is if you can even find one on the market to begin with!

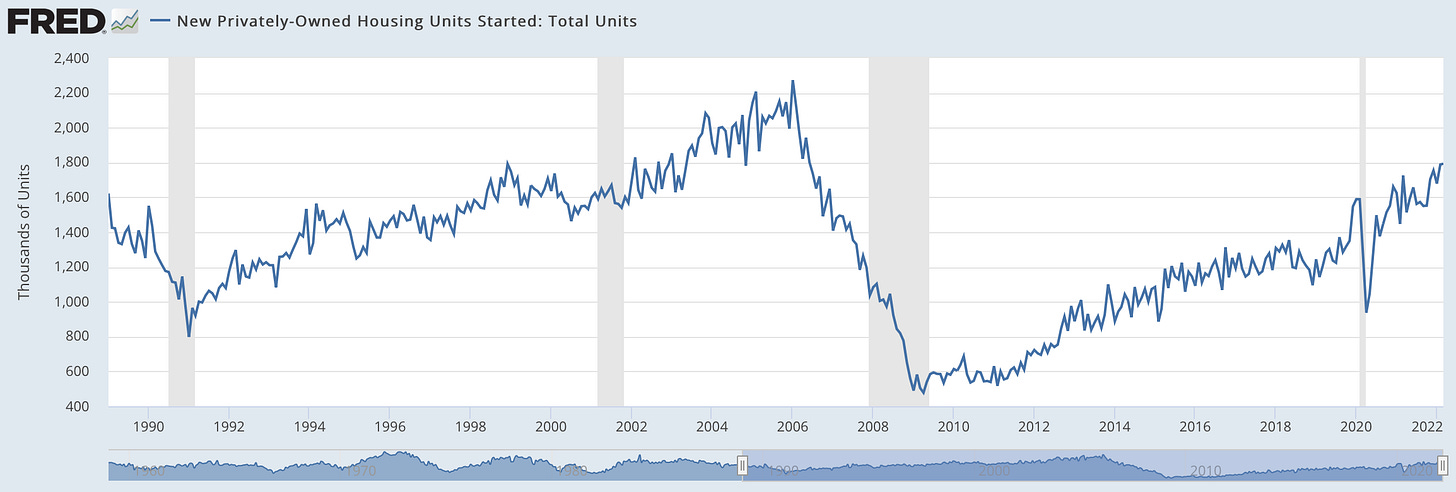

The second point is that we had a significant period of underbuilding at the beginning of the last decade. According to Trading Economics, from 1959 to the current day the country has averaged about 1,433,000 housing starts on an annual seasonally-adjusted basis. To provide some context, the chart below shows the stats for new housing starts over the past 25 years. What is evident is that there was a period of about seven years following the Great Recession that new-home construction was significantly below the historical average of 1,433,000 new homes:

We are dealing with the consequences of that period of underbuilding now. Why did we underbuild as a nation during that time? Certainly the country was still emerging from the economic recession and demand for new homes was much lower than it is today because many consumers were in rough shape. But then, as now, there were also workforce challenges including a labor pool without enough construction workers, builders, and contractors. Banks were also not extending liquidity to homebuilders as readily back then because of new banking regulations and justifiable concerns about risks - after all, a lot of banks big and small took heavy losses with the collapse of the housing market in 2008.

One final note on this point about underbuilding, if you zoom in on the chart above to show just the past five years, a notable drop-off in new home construction is clearly evident in the spring of 2020, which is right when COVID was initially hitting the United States. At that time people thought the housing market was in real peril and both buyers and builders pulled back significantly. Of course, the opposite actually happened and the market roared back after a momentarily lull. But in a market with such strong demand today, that several-month period of underbuilding in 2020 continues to have ripple effects today. The chart below shows just the past five years of new-housing starts, with the drop-off in the early days of COVID clearly evident:

3. The Conversion of Homes and Monthly Rentals to Nightly/Vacation Rentals

By one calculation, there are 660,000 AirBNB properties in the United States (among four million worldwide). The popularity of these types of rentals surged during the pandemic as many travelers were reluctant to go to a more traditional hotel. Consumers have also become more tech savvy and there is a cultural shift where younger consumers are just more trusting of these types of arrangements. I am planning a more comprehensive article at some point about the rise in popularity of vacation rentals and some of the implications for local communities. I am really seeing local attitudes change on the question. Communities throughout Maine, for example, have been ruminating on ordinance changes to block property owners from converting their properties to daily/nightly rentals. Bar Harbor, at the doorstep of Acadia National Park, did this just last year, and numerous other communities seem to be following suit.

The issue for these communities, of course, is that every property that is converted to a nightly rental is one fewer property available for a full-time resident whether that be as a primary homeowner or a renter. For Bar Harbor residents who voted to make the change, they were tired of seeing families, retirees, and others not have homes to live in on a full-time basis. Local employers were frustrated with a lack of month-to-month workforce rentals. I expect more and more of these ordinances to be enacted in the months to come, to the detriment, of course, of some property owners who want to rent out their homes as vacation rentals and who are often able to generate robust cash-flow from these types of units. But again, more on all of this to come in a future article. What is good for one group is often not for another, hence the inherent tension in these types of policies.

I happened upon the tweet below recently, and while I cannot vouch for its authenticity/veracity, I suspect it is generally accurate:

It is easy to hypothesize that if every single orange dot above were a traditional monthly rental or single-family home, the housing inventory would be a lot looser, which would be advantageous to renters and aspiring homeowners.

4. More Renters with Resources

For all the talk of competition in the home buying market, there has also been increased competition in the rental market. This has been driven by several variables, most significant of which is that the pandemic sparked a lot of moving around of both white collar employees who can do their work from anywhere, self-employed individuals who can do the same, and retirees who are not anchored to any one geographic area anyway. A lot of these people have significant resources and are more capable of paying higher monthly rents. On top of that, many of these people are moving from high-rent areas like California and New York and their perspective on what actually constitutes “high rent” is wildly different than what those in a local market feel. I have seen this play out here in Bangor: someone moves from San Francisco, for example, where the average monthly rent is typically north of $3,000/month, and they pay $2,400/month for a high-end apartment here. That is the top end of the rent spectrum in Bangor, and people moving here and to other places like it are willing and capable to pay these higher amounts, which drags the entire rental market up in price. And there are just more of these people in the renter pool right now, which is one of the reasons things are so tight.

5. Households Are Getting Smaller

I see a fifth reason why rental vacancies are so low, which is that there are more households to begin with, and the the size of the average household is getting smaller. Consider this: according to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2001 there were 108 million households in the United States. Twenty years later in 2021, there were nearly 130 million, an increase of about 22 million additional households. The average size of the American household was 2.58 people in 2001. As of last year it was 2.51. That might not seem like a significant change, but multiply that difference across the entire economy and it means there are just more people in the housing pool than in previous times.

In fact, the average U.S. household size has been pretty steadily declining since the statistic was first tracked in 1960:

There are a lot of reasons to speculate about why households are getting smaller: less intergenerational home arrangements, the increased prevalence of divorce leading to multiple households, rising affluence allowing for more renters to live alone rather than with roommates, and the general decline in the number of children per parent/couple. But whatever the reasons, more households with fewer people living within each one means there are more people who need their own homes, which I think is one of the reasons why the rental market is tight. Then again, as evidenced by the chart above, the average household size has, in fact, been steadily declining and there were periods in the rental market over the past forty years that vacancies have actually been higher, so this is probably not the most explanatory variable, but it is still relevant, I think, especially in the context of the other variables noted above. If the economy does enter a recession and economic conditions for tenants deteriorate with a weakening labor pool, it will be interesting to see if the average household size increases as people look to share costs in a weaker economy by living together.

What Comes Next

There are reasons to think that, at some point at least, things might loosen up in the rental market. These things do tend to cycle, although as noted above the vacancy rate hasn’t been as low as it is now since the mid-1980s. More optimistically, the annualized rate of new-housing starts in March 2022 was 1.793 million, which is notably stronger than the historical average of 1.433 million. In fact, the current rate of new construction is the strongest it has been since June 2006:

The next data on new housing starts, which will be for the month of April, comes out on May 18th. If construction can stay at such a strong level for an extended period of time (like at least the next 3-5 years), we might get enough inventory to loosen up the rental market. For more discussion about building trends in multiunit residential rental properties, which is its own interesting story and a key part of the housing conversation, stay tuned for future articles.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com. Follow Ben on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

Wishing a Happy Mother’s Day to all the moms out there, including mine! Here is a picture of my mom and me during my stint as a Fenway Park Tour Guide in 2006-2007. I love you, Mom.

Have a great week, everybody, especially all the moms.