Thank you for reading The Sunday Morning Post! If you would like to receive my articles each Sunday morning, just click Subscribe below.

America's elite universities have been under heavy scrutiny in recent months. Most notably of late was the tepid performances that were uncaring and excessively legalistic by three university presidents before Congress in the wake of the October 7th Hamas terrorist attacks. Consternation about the line between free speech and hate speech on campuses has roiled student groups, alumni organizations, and others connected with universities big and small, as have accusations of plagiarism and professional impropriety by key leaders most notably at Harvard. Campuses remain mired in disagreement, sometimes toxically so, and major donors have signaled their withdrawal of support of some of these heralded institutions to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars.

All of that is enough to cause a great deal of anxiety in the boardrooms and development offices of these great schools and others like them around the country. But there is another looming crisis that will hit like a slow moving whirlwind over the next 10-15 years, and this one will impact schools big and small from local independent colleges to flagship state universities and everyone in between. The crisis is one of demographics, made all the worse (at least from the perspective of college administrators and financial offices) by changing perceptions of the value of a four-year degree and whether taking on significant debt to achieve said degree is worth it.

“Demographics are Destiny”

The quote above is most commonly attributed to 19th century philosopher Auguste Comte, with the point being that birth rates and immigration impact societies and economies large and small. What’s the connection to university campuses today? Well, the demographics for colleges and universities are trending in the wrong direction, most notably here in the Northeast where birth rates are lower than in other parts of the country; there are not enough young people to fill all of these college classrooms.

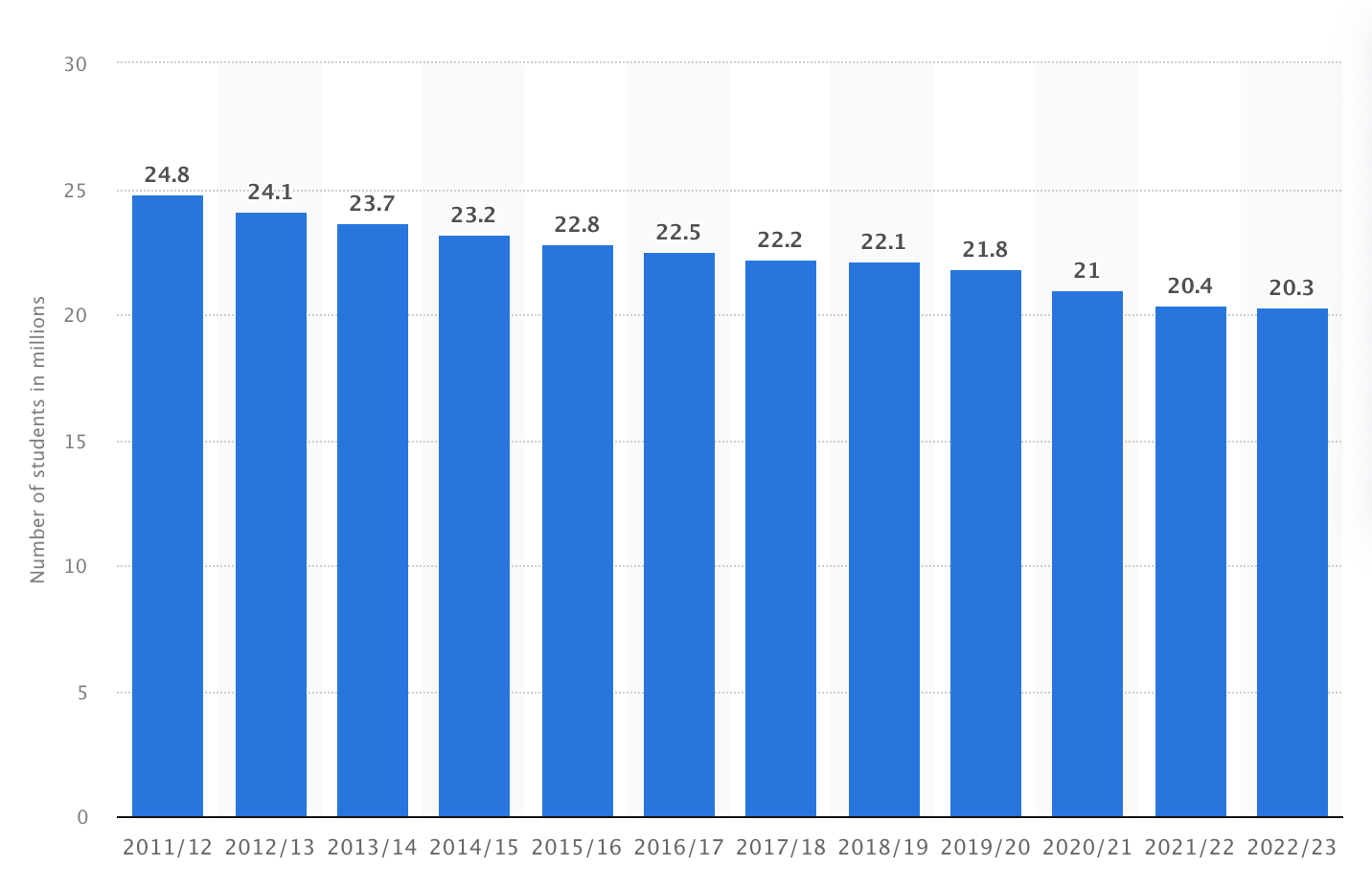

The chart below shows the number of enrolled college students in the United States going back to 1970. College enrollment peaked in 2010. The steady decline since then is evident:

As a quick aside, the above is not a great chart in that the horizontal X-axis starts in increments of 10 years but then switches to five years and then increments of one year. Nonetheless, it illustrates an important point, which is that the number of college students is trending downward after multiple decades of fairly steady increases. This trend has accelerated since 2020 as the number of college students declined even more rapidly during the COVID years and has not since recovered.

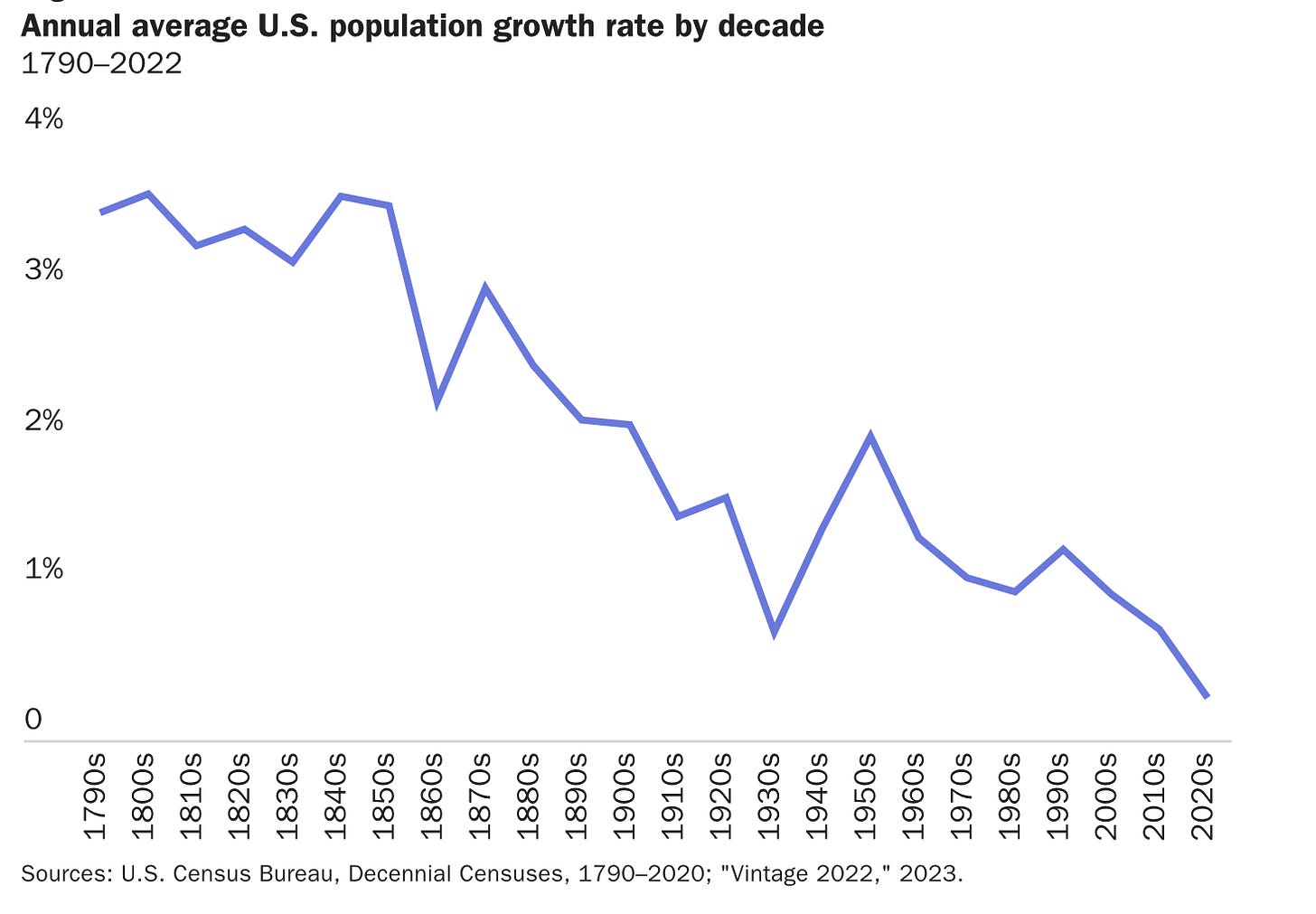

Why the decline since 2010? For starters, birth rates in the United States are positive but relatively flat. In other words, the population is not shrinking, but there is also not a surge of newly born Americans coming of age who might then attend college. The chart below shows annual population growth by percentage in the United States going back to nearly the founding:

Birth rates have declined for a variety of reasons. The trend from an agrarian economy to an industrial one has meant less need for large families with many children to work on farms and other rural family businesses, for example, although a more notable reason is undoubtedly the expanded use of contraception. In addition, over the last 40 to 50 years, having more women in the workforce has meant more two-parent working families, many of whom are often content with one child or perhaps two, or in having no children at all. The significant increased prevalence of divorce over time has also likely led to fewer children being born, although there are plenty of single-family households with multiple children for sure.

But back to the topic at hand: with non-robust population growth, colleges and universities are not seeing a swell in enrollment. The story goes beyond that, however. Not only is there minimal population growth, but among those who could enroll, fewer are choosing to do so. According to The National Center for Education Statistics, the college enrollment rate for those age 18 to 24 declined from 41% in 2020 to 38% in 2021. A big part of that downturn is definitely that 2021 was an especially bad year to be on a college campus because of COVID-19 and the related restrictions, so a lot of would-be students decided to just not go. Plus the labor market has been so strong over the past few years. Why go to college when you can get a job fresh out of high school and make decent money instead? It’s a fair question, and one that a lot of would-be students have been answering by simply joining the workforce instead of going to college.

All in all, an easing up of population growth plus a decline in the number of those who are choosing to enroll has added up to fewer students on campus to the tune of 4.5 million fewer students in the 2022/2023 academic year compared to 2011/2012 according to data from Statista, as shown in the chart below:

The Tuitions Are Too Damn High

There are other reasons why fewer young people are choosing to attend college. First and foremost is the cost. According to the Education Data Initiative, college tuition increased by an average of 12% annually from 2010 to 2020, the fastest annual rate of tuition inflation of any decade since the statistic started to be tracked. It is no surprise then that this decade also saw a decline in the number of students. We may not think of a college education as a typical widget that is susceptible to the usual economic principles of supply and demand, but the story over the last 10-15 years suggests that it is: as tuitions rose, enrollments declined.

There is also now a whole generation of parents who may have earned college degrees themselves as they were told was necessary to do, but who were saddled with tens of thousands of dollars of student loan debt in the process. According to data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve, total student loan balances nearly quadrupled from a level of $481 billion in 2006 to almost $18 trillion in 2020. Student loan debt has held many of these young parents back from buying homes, building up their savings, and expanding their families. But for those who have kids who are now aging into the college-eligible demographic, many of these parents may be using their own stories as a cautionary tale and advising their kids to not necessarily pursue that traditional track of going to college after high school.

What it Means for Schools

The number of colleges and universities in the United States is, in fact, on the decline. Per The Center for Education Statistics, there were 3,931 Title IV degree-granting institutions in 2020 (which is a fancy way of saying colleges and universities that are eligible for federal student aid), down from 4,599 in 2010. That is quite a drop. Some schools have folded altogether, while others have merged or been subsumed into others. Previously independent Wheelock College in Boston, for example, became a part of Boston University in 2018.

Also on the decline (sort of): tuition. For the 2023 calendar year, college tuition inflation was 1.2%. While that is a positive number, it was less than the overall inflation rate of 3.4%, which technically means that tuition declined relative to the overall cost of goods and services last year. Are tuitions likely to continue to decline? You bet. The factors that have led to an easing up of tuition are only like to become more entrenched in the year ahead including consumers (in this case, college-eligible students and their families) opting not to enroll because the costs are still very high. The labor market remains quite strong especially for entry-level jobs, too, so plenty of young people are likely to continue going straight into the workforce. For all these reasons, there is a great questioning right now of the value of a four-year degree, and that conversation is not going away anytime soon.

Some schools especially state public institutions have frozen tuition, which is usually framed as a missional effort to give students and families a break amid a weak economy and inflation in other areas of spending. While these announcements are usually met pretty positively (and why wouldn’t they be?), the simple truth of the matter is that it is also in the interest of the schools to limit tuition hikes otherwise they will price themselves out of the market. Tuition freezes are as much about self-preservation of the institution as they are about giving the kids (and their families) a break, in my opinion.

The other challenge for colleges and universities is how to compete for a declining number of students. Do they actually decrease tuitions, which might attract more students but also takes away some of the school’s existing cash flow? Do they invest in new facilities and special amenities, the risk being these things themselves often cost a lot of money and the return on investment is sometimes questionable or at least hard to quantify? Do schools expand academic offerings, or consolidate to a few areas of special focus? I imagine it is a very challenging time to be on a university board of overseers these days, let alone be a college administrator.

The Exception

There is one place in post-secondary education that is bucking the trend: trade schools. According to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, student enrollment in construction trades courses was up by 19.3% from Spring 2021 to Spring 2022. Culinary trades programs were up by 12.7% while mechanic and repair enrollment was up by 11.5%. This is a great success!

Trade school education is beginning earlier and earlier, too. Here in Bangor, Maine where I write from, a school called United Technologies Center (UTC) is educating high school students in the trades, technical fields, and other career paths. The program is funded by 39 local communities in the area; it’s a great example of regional collaboration. Area high schools can send their students to take a portion of their coursework at UTC, which is a good fit for students who already have an idea they might want to work in the trades post-graduation or who may not do as well in a traditional high school classroom setting. It’s no surprise that UTC has seen its numbers grow significantly in recent years, and is now talking about an expansion.

Final Thoughts

Not to diminish the very real emotions people feel about hot button issues on campus right now at places like Harvard, Penn, and MIT, but some of that is Culture War battles that will likely fade over time. The larger question for colleges big and small about demographics and changing perceptions of the value of a college degree are likely to last. Higher education as an industry, such that it is, is in a period of major disruption. More consolation is likely in the years to come, as well as pressing questions about how schools allocate their resources. In the meantime, enrollments are likely to continue to decline as the demographics continue to trend like they have been in recent years.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

Weekly Round-Up

The internet….curated for you! Here is what caught my eye around the web this week.

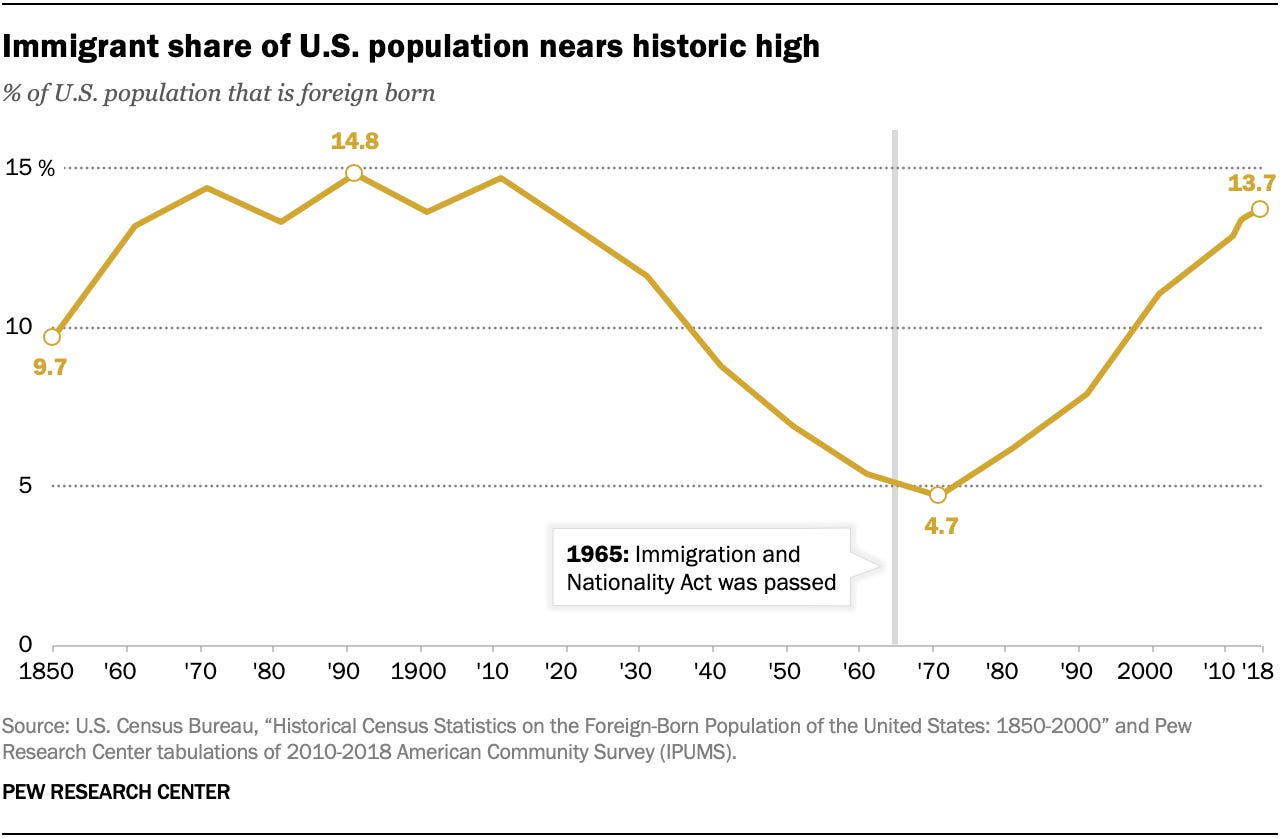

Related to today’s topic, as of 2020 13.7% of people in this country were foreign-born. This is up from a low of 4.7% in the early 1970s, but on par with most of the 1800s and early 1900s. The chart below via Pew Research shows the historical trends.

The average 30-year fixed rate took a pretty big jump at the end of the week and is now pressing back towards 7.00%, per Mortgage News Daily. The culprit this week? A strong jobs report, which suggests the Fed might continue to hold off on interest rate cuts. The 52-week range for mortgage rates is 5.99-8.03% with rates closing the week at 6.92%, almost exactly in the middle.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell says it’s not his fault that home prices and rents have risen so much, instead blaming a lack of construction of new units, which is outside the Fed’s purview. Asked if he is concerned about high home prices during a Wednesday press conference, he responded by saying:

Our statutory goals are maximum employment and price stability, and that's what we're targeting. We're not targeting housing price inflation, the cost of housing or any of those things. Those are very important things for people's lives. But those are not the things we're targeting…

…On top of that, we have longer run problems with the availability of housing. We have a built up set of cities and people are moving further and further out. So there hasn't been enough housing built. And these are not things that we have any tools to address.

Yes, Christmas is still nearly 11 months away, but freight companies are already telling lawmakers that conflict in the Red Sea could impact the 2024 holidays. Read more via John Gallagher at Freight Waves.

Per Bloomberg, rents have dropped for eight straight months. Sorry, the Bloomberg article is behind a paywall, but you can read my non-paywalled Rental Market Preview here if you missed it in January.

One Good Long Read

The story of a midwest couple who won over $27 million in the lottery over nine years using the oldest tool in the book: math. The article is “Jerry and Marge Go Large” in The Huffington Post from 2018. A highlight:

Studying the flyer later at his kitchen table, Jerry saw that it listed the odds of winning certain amounts of money by picking certain combinations of numbers.

That’s when it hit him. Right there, in the numbers on the page, he noticed a flaw—a strange and surprising pattern, like the cereal-box code, written into the fundamental machinery of the game. A loophole that would eventually make Jerry and Marge millionaires, spark an investigation by a Boston Globe Spotlight reporter, unleash a statewide political scandal and expose more than a few hypocrisies at the heart of America’s favorite form of legalized gambling.

Fair warning, this article is REALLY long. If you have access to a printer, my suggestion is to print it, grab a cup of coffee or tea, and cozy up for a good 30-40 minute read.

Happy reading, everybody! Have a great week!

Very interesting topic and great to see the statistics laid out! As much as I want to see my alma mater UMaine succeed with enrollment, as it relates to real estate and inflation, the higher percentage of and higher enrollment numbers of students in trade schools is a welcome sign. In my experience, there is a labor shortage in the trades, especially here in Maine. As a result, housing costs are higher either because tradespeople can demand higher rates or projects drag out and holding costs accumulate due to labor demand exceeding labor supply. It is be a great time to be a young or otherwise entrepreneurial tradesperson! Starting in high school, and beginning immediately after, someone could achieve upper level trades licenses by age 22-24 and open their own trades business or solo effort. Their yearly income would rival some of the best paying jobs for entry level college grads, all without the cost of college and lost income for 4+ years while in college. Even if the college grad job does pay better, it would take quite a few years to catch up to the 4 extra years of income. The quality of life, impact on physical health, etc. between post college employment and the trades is a more complex topic, but strictly financially it is not surprising why more young people are not seeing the value proposition they once did with college degrees.

Here is a note for the town planning profession.

The advent of single purpose zoning to create the dormitory suburb went along with the institutionalization of learning. Gone was the master-apprentice relationship with the advantage of a low student number to teacher ratio and the motivation to solve meaningful problems as part of the act of creation on a daily basis.

Along with institutionalized of learning we got tokenized 'work experience' for a couple of weeks a year if one was lucky.

It's desirable to end the dysfunctionality of single purpose zoning so that we can marry work with the home again, reduce our reliance on cars and let kids find mentors that they are keen to work with for next to nothing because of their enthusiasm to learn and to create.

The decay of institutionalized learning will be ongoing because the evils attached to single purpose zoning are becoming apparent. The long commute to work, the supermarket, the hospital, the beach, to sport, to school, the child care centre, to meet the family and a myriad of other reasons to get behind the steering wheel is turning into a disaster. We need to plan a city where all the things we need are within walking distance and as many as possible can work from home.