The Futility of International Law

Author’s Note: if you’ve been watching the news at all this week, it feels trite to write about anything other than the situation in Ukraine. I’ll be back next Sunday with some more typical content, but for today, a few thoughts on the role and efficacy (or lack thereof) of international law and economic sanctions.

The Futility of International Law

In the aftermath of World War I, a conflict in which over 15 million people died with many millions more injured or maimed, the leaders of the world’s key powers including United States President Woodrow Wilson sought to establish a framework that would prevent such a horrible conflict from happening again. What emerged by 1920 was the League of Nations. But, of course, “The war to end all wars,” the First World War most certainly was not, as less than two decades later the world would be thrown into a second and yet much larger conflict that neither the League of Nations nor its respective members could prevent or forestall. Over 70 million people would die during World War II, an estimated 3% of the world’s population at the time.

So what happened? And why was the League of Nations so ineffective at stopping the next great global conflict? Volumes upon volumes have been written about this, but the League failed for a combination of reasons. First, then as now, citizens of countries around the world are inherently isolationist. People are naturally skeptical of being taken advantage of by any sort of international body or of being drawn into international disputes that do not directly affect them or their country’s interests.

This is particularly true in the United States, who tried for quite a long period of time to stay out of both World Wars I and II before being dragged into both. Isolationism is baked into the fabric of this nation. Indeed, it is a part of the founding story of the country. It was none other than George Washington in his Farewell Address to the Nation who said:

Why, by interweaving our destiny with that of any part of Europe, entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor or caprice? It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.

This philosophy has kept the United States out of a good number of so-called foreign entanglements, but our lack of involvement in various international causes has also undermined the effectiveness of those efforts. This is true even today with the United States being reluctant and often refusing altogether to participate in global initiatives on topics like climate change and human rights, among others.

And in fact, 100 years ago, despite the fact that President Wilson was a proponent of the League of Nations so much so that he won a Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts, the Unites States did not actually join the League. Isolationists in Congress rebuffed the President and refused to ratify the treaty that created the League of Nations, worrying that the United States’s involvement would draw the nation into international conflicts in which the United States had no vested interest.

It’s impossible to say what would have happened if the League of Nations had been stronger. Given just how diabolically evil Adolf Hitler was and the confluence of post-World War I variables that laid the groundwork for the Second World War, it is likely in many ways that World War II was inevitable. However, while there are costs of participating in a system of international cooperation, but there can also be costs of not. One does wonder if a stronger international framework of laws, justice, and consequences could have dampened the intensity of the conflict, perhaps shortened it, and significantly lessened the astronomical cost of human lives, both military and civilian. In other words, what was the cost of isolationism?

Economic Sanctions

The other inherent weakness of international law is that organizations like the League of Nations and its successor, the United Nations, do not have standing militaries of their own. It is hard to enforce pacts, treaties, and decrees with no threat of force to back them up.

That is one reason why economic sanctions, which do not require military deployment, are so common. In fact, President Wilson himself said in 1917:

A nation that is boycotted is a nation that is in sight of surrender. Apply this economic, peaceful, silent, deadly remedy and there will be no need for force. It does not cost a life outside the nation boycotted, but it brings a pressure upon the nation which, in my judgment, no modern nation could resist.

But do sanctions work? The Peterson Institute for International Economics published a paper in 1997 that suggested economic sanctions work about 35% of the time, but the criteria for what is considered to be effective are vague. It is also impossible to prove a counterfactual - what would have happened absent the economic sanctions and would that have been better or worse than what did occur? It’s often impossible to say.

Certainly countries that have been economically isolated over the past half century have had dire economic impacts to them with North Korea being the most obvious example, and economic sanctions are popular among policymakers because there is no direct deployment of men and women in the armed forces as there is in a typical war setting.

The Situation in Ukraine

On the question of whether economic sanctions are currently working in Ukraine, the short-term answer is that obviously they did not prevent Russia from invading so one could argue the sanctions have not been effective. However, there is a long way to go before this question can be fully answered. For example, the Russian stock market dropped 33% on Thursday alone, one of the worst single-day drops of any market anywhere in the world in modern history (although it did bounce back a bit on Friday). Russian currency has plummeted in value and there is a real risk of a banking crisis in Russia as Russian citizens make a run on banks to pull their money out. These feel like actual consequences that will actual impact the war footing.

There is a quantitative reality that Putin and his military will be up against shortly. Russia is only a moderately wealthy country and wars cost a lot of money. In fact, by GDP Russia is only the 11th wealthiest country in the world, which puts it in a similar category as South Korea and Brazil. If California, Texas, and New York were their own countries, they would all be ranked as more economically robust than the entire nation of Russia. If Russian currency is not worth anything and the Russian government is frozen out from worldwide commerce, their invasion of Ukraine will be in peril because their liquidity, their ability to restock and refuel, and all the logistics of transportation will be in jeopardy.

Indeed, there are already images on Twitter of Russian tanks running out gas and sitting, abandoned, on the roads leading to Kiev as the Russian military faces stiffer resistance than was initially expected:

What Comes Next

It is unlikely that any framework of international law will stop the Russian attacks in Ukraine. Ukraine is not yet a member of NATO, so NATO appears to be unwilling to lend boots-on-the-ground or air support other than by providing weapons and supplies. The United Nations is effectively neutered by the fact that Russia itself sits on the permanent security council along with the United States, United Kingdom, France, and China, which gives them veto power of any U.N. resolutions. In fact, on Friday, Russia vetoed a U.N. statement “deploring” the Russian invasion of Ukraine; the United States, United Kingdom, and France voted for it with China abstaining. Even still, the vote was only on a statement and was worth about as much as the paper it was written on as it would not have come with any military support for the Ukrainian people anyway.

Nor are there are any international courts of law that could take up a conflict between Russian and Ukraine. For starters, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which meets in The Hague in The Netherlands, only takes cases that are submitted by two countries who agree to have the court adjudicate it, which is, of course, simply not going to happen in the case of Russian vs. Ukraine, and second, the ICJ has no enforcement mechanism over its decisions anyway so rulings are routinely ignored by the sparring parties.

So that leaves the hope of the Ukrainians in the economic sanctions and other non-military steps that the rest of Europe, the United States, and others can deploy. Of course, the loophole in the sanctions, as some have already pointed out, is that so far they have been fairly weak: Per Alan Cole in Slate:

The sanctions also have a glaring weakness: They largely spare Russia’s all-important energy sector, the backbone of its entire economy, and its agricultural center (the country is a major wheat exporter).

The NATO allies have chosen to leave these sectors alone in order to minimize the impact on Western consumers. This need—driven especially by German consumers, but also substantially by the Biden Administration’s fear of raising gas prices and fueling inflation in the U.S.—forced the U.S. Treasury Department to blow a hole in what would otherwise have been an effective form of financial retaliation.

For sanctions to be truly effective, they have to hurt. Saturday evening, though, it appeared that the United States and its European allies were ready to up the ante on sanctions against Russia, including their removal from the SWIFT banking system, which is an international payment system crucial to global commerce. These allies also seemed willing to pursue more sanctions against individual wealthy Russians aboard. Even amid such a perilous situation it is amusing to think of the wealthy Russian oligarchs specifically targeted by sanctions who could now see their homes, boats, and jets seized or frozen. Whether this will lead them to turn on Vladimir Putin remains to be seen, however.

The hope today versus in previous times when the effectiveness of economic sanctions was more questionable is that the world is much more economically linked than ever before. Sure, countries traded with one another in 1920, but not to the extent that they do today. Most countries around the world have a vested interest in economic stability and war is unquestionably a destabilizing event.

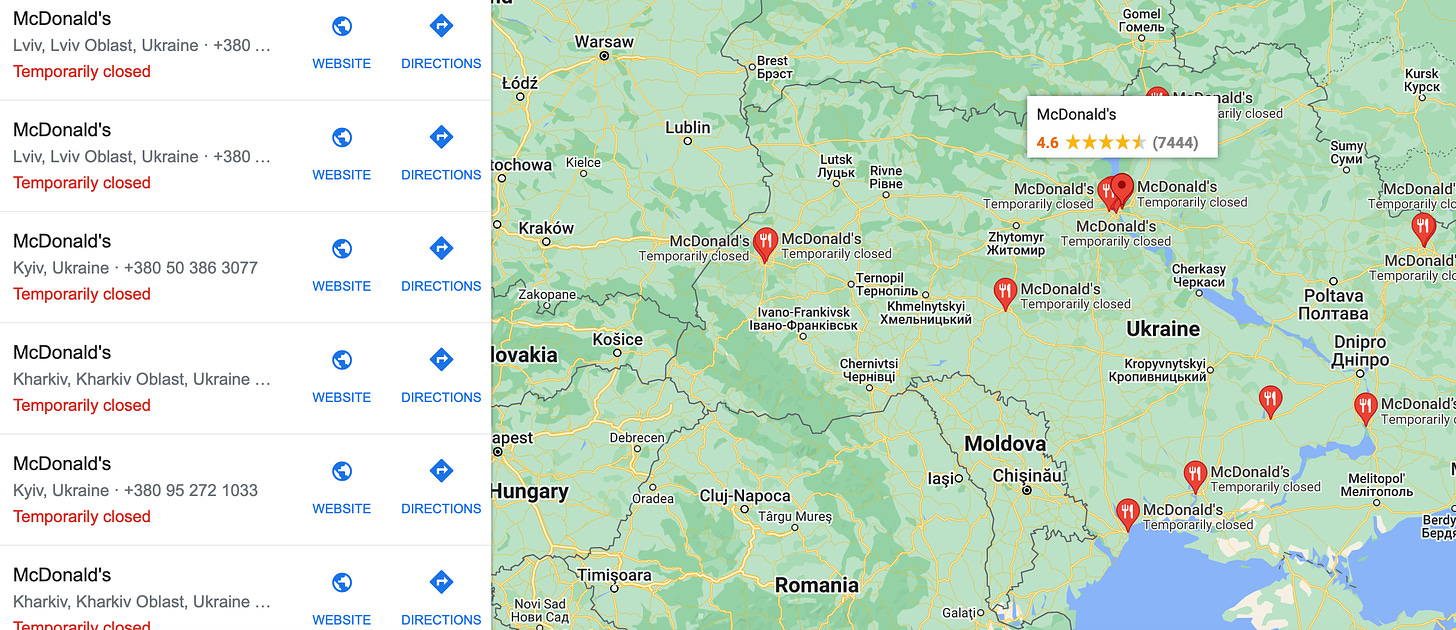

In 1996, Thomas Friedman posited “The Golden Arches Theory of Conflict Prevention,” which said that no two nations with a McDonalds would ever go to war with one another because the economic costs to each would be too great. Although this theory has been fairly questioned, the general conclusion that economic linkages are preventative in nature to open conflict is valid. There are McDonalds in both Russian and Ukraine, however, and war is upon them, although for understandable reasons this particular weekend all of the McDonalds in Ukraine are closed.

One Final Question

As the world discovered at the outset of World War II, the peril in isolationism is that evil forces can grow power and influence unabated. There are always costs of international intervention, but sometimes the costs are greater of staying on the sidelines. The stories coming out of Ukraine of heroism, courage, and honor are inspiring to say the least. The Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has rightfully gained worldwide acclaim for his bravery, including the memorable line, “I need ammunition, not a ride,” in response to efforts by the United States to extract him safely from his country. Watching a war play out in real time on T.V. and Twitter has been fascinating, troubling, and eery, but that is one of the other main differences today as compared to previous times: stories and images of Russian atrocities go instantly viral, which swells support for the Ukrainian underdogs.

What is the cost to the United States and its allies in Europe of not becoming more involved? The hope, of course, is that a combination of sanctions and military supplies will be enough, but those sanctions will need to cut to the Russian core. Because the world is so economically linked, those sanctions are likely to hurt ourselves and our friends in Europe as well at least in the short-term. How much are we willing to withstand to support the freedom and self-determination of the nation of Ukraine? Time will tell over the coming weeks.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006 where he majored in Government/International Relations. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com. Follow Ben on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

One Quick Read: when did World War I and World War II get their names? Short answer: not until the 1940s. Read more at History.com.

Author’s Note: no Weekly Round-Up this week. Apart from closing monitoring the news all week, I have spent a good deal of time at our local high school basketball tournament with my kids. See you next Sunday for more. Have a great week, everybody.