The Math of the Housing Crunch

A crisis 15+ years in the making

If you feel like the housing crisis has gotten worse over the past few years, your perception is correct. I do not mean to imply that the pre-2020s market for homes and apartments was some sort of idyllic landscape of inventory and equilibrium, but things definitely got worse in 2020 specifically. Housing in its various forms is now high on the radar of policymakers at all levels of government, who have been inundated by constituents identifying rising rents and a frustrating home market as top concerns.

On the rental front, rents have historically increased at a 3-4% average annual clip going back to the 1950s. But per CPI reports, rents inflated by 8.3% in 2022 and by 6.5% in 2023, both outpacing general inflation in those years. An average rent of $1,200/month at the beginning of 2022 would be $1,384/month just two years later at that trajectory. Some markets have seen rents rise by even much more than that.

The bump in the chart below shows how abnormal this increase in rents was, at least in terms of recent history. Each blue column is the monthly increase in rents per the CPI. There was an initial drop at the outset of the pandemic, but by early 2021, rents were starting to surge:

The single-family home story has been arguably even more dire in recent years, at least mathematically so. The median home price according to the National Association of Realtors in 2021 was $357,100; two years later in 2023 it had increased to $394,600. While that is only an increase of 10% in two years, which is very much in line with historical averages, the kicker for would-be homebuyers is that the average 30-year interest rate increased from 3.01% to 6.88% in that same time. Take the modestly higher median home price and a significantly higher interest rate, and the average mortgage payment increased from $1,206/month in 2021 to $2,075/month in 2023, an increase of 72% in just two years!

How did we get here? And how does this crisis ease? To answer the first question, we need to go back 15 years to the Great Recession. To answer the latter, one only need to look at some figures from the past year.

A Crisis 15+ Years in the Making

To understand why home prices and rents increased so much from 2020-2022, you must first go back to 2007. That is when home prices started to tumble at the outset of the Great Recession. The problem was not the recession itself; in fact, going back to World War II, the United States has experienced a recession on average once every 6.5 years. The problem was also not the stock market drop, or the surge in unemployment, although to be sure those things were all decidedly bad. The problem with this particular economic downturn, and why it is relevant to today, is what it did to the construction market, which was to significantly curtail activity for multiple years in the aftermath of the initial drop. Consider the chart below of new home construction going back 40 years:

From the early 1990s to the mid-2000s, there were 1.0-2.0 million new homes built every single year. The sharp drop off during the Great Recession is evident in the chart above. What is notable, though, is that the rate of new home construction never catches back up to pre-2008 numbers in the years that followed. In March 2006, the seasonally adjusted rate of annualized home construction was 1.9 million new homes per year; in December 2023, the most recent month for which data is available, the rate was almost half of that even after more than a decade of recovery.

The root of the single-family home crunch is this drop in construction. I attribute the drop to four variables. First, demand among would-be homebuyers was way down for several years as people’s finances were commonly in disarray in the aftermath of the collapse. Second, a lot of homebuilders got burned in the Great Recession, some of whom actually went bankrupt and others of whom significantly curtailed their activities or moved into other types of construction. Third, banks big and small took significant losses from 2007-2010, and bankers became gun-shy. And lastly, because banks and mortgage brokers did a lot of bad home loans from 2000-2007, new banking restrictions sought to reign some of that in, thereby dampening demand for new home construction (and the loans that go along with it) during this time.

Jump ahead to 2020, however, and you have a whole generation of would-be homebuyers coming of age and looking to buy at a moment when the inventory of new homes to buy was significantly below historical levels because of this extended period of under-building in the years prior. Moreover, in 2020 specifically, would-be homebuyers were boosted by stimulus funds that strengthened the household finances of countless Americans. Spending in other areas of the economy such as travel and entertainment was significantly curtailed due to pandemic restrictions, so there were suddenly vast swaths of people who had the available resources and wanted to buy homes, but could not because there were not enough homes available, hence the price surge.

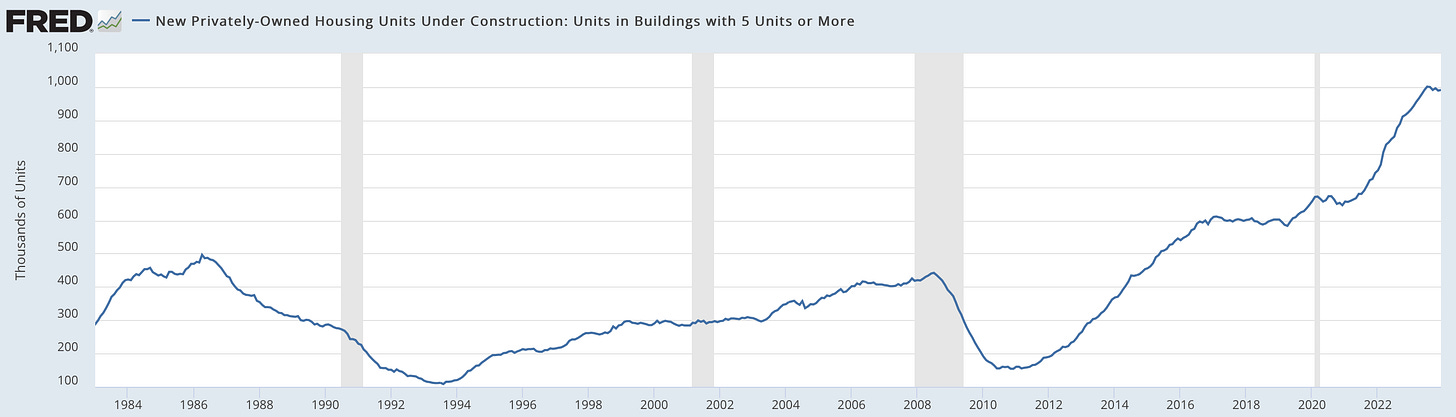

The story is a similar one on the rental property side of things, although there are a few key differences (more on that later). The chart below shows newly constructed 5+ unit rental properties going back 40 years:

The trajectory is a bit similar in that there was a drop-off during the Great Recession and a troughing out over the next few years. The same crunch with rising prices we saw in the single-family home market by 2020 is also applicable to the rental market due to this period of under-building from 2009 onward. Robust demand for rents met limited supply in 2020, hence the rise in prices.

Household Formation

There is another reason why prices for homes and rents jumped in 2020, however, and that is a question both sociological and mathematical: there was an abnormal increase in the number of households nationwide from February 2020 to August 2020. Check out the bump in the chart below almost immediately at the outset of the pandemic (the brief recession the economy experienced starting in March 2020 is highlighted in gray):

What that bump represents is an increase in the number of households nationwide from 123.9 million in February 2020 to 127.3 million by August 2020, an increase of 3.6 million additional households in just six months. And as you can see from the aftermath of that bump, after a brief settling down in household formation in the fall of 2020, the upward trajectory resumed to an estimated 131.3 million households by December 2023. That is an increase of 7.4 million additional households in just under four years. This boost in household formation combined with the other variables noted above that were unique to 2020 (most notably the diversion of spending FROM areas in the economy that were shut down TO housing plus the stimulus and other financial support people were experiencing during this time not to mention a strong labor market) is what led to a surge in both home prices and rents, particularly on the heels of a multi-year period of under-building coming out of the Great Recession.

Why were so many new households formed during this time? I speculate that it because a lot of people moved out from living with roommates during COVID, plus as noted previously the labor market was surprisingly strong and people were boosted by stimulus, giving them the financial stability to live alone or with fewer roommates. I also think a large number of college students moved out of dorms and off campus during this time, thereby creating new households (yes, even a college student living alone counts as a household!).

Add onto this inventory crunch of new homes the reality that many existing homeowners are staying put, a phenomenon I call the Golden Handcuffs, and the inventory situation looks even more dire. Why give up a pre-2022 interest rate of 3.0% or better to move into a market where prices are higher, choices are fewer, and interest rates are MUCH higher? People are just not moving, so the market is lacking the normal turnover of homes that engenders a healthy marketplace.

What Comes Next

It may sound overly simplistic, but to ease the housing crunch we need to build more houses and apartments. Single-family homes, multiunit properties, Accessory Dwelling Units (ADU’s), tiny home communities, low-income housing developments, high-end units, workforce housing, mobile home parks: you name it, we need it. As the supply of available units increases, it will ease all of this upward pressure on prices that we’ve seen over the past few years.

In fact, there is already some evidence that this is happening, particularly in the rental market. The chart below should give some hope to policymakers, housing advocates, and tenants alike and should perhaps cause some concern among existing rental property owners (although, to be sure, regional variations are key and this is simply a chart showing national numbers). The trajectory of multiunit rental units under construction shows a current surge:

The trajectory is clear. There is a huge swath of newly constructed rental units coming online over the next two years, in fact the most in over 50 years. This will ease rents by giving tenants more choices of where to live. There is already evidence that rents are starting to decline nationwide, with average rents down for the past eight straight months.

The single-family home construction market is a bit similar to the one for rental units, albeit it with one caveat; although new home construction has similarly been high over the past couple years, it is still below historical levels and there has been a drop-off in recent months. The same interest rate frustrations experienced by buyers of existing homes is generally applicable to people who are building a new home; unless you’re paying cash, most new home construction needs to be financed somehow and those interest rates are high right now, which is dampening activity.

The other thing that will loosen up the home market and bring prices down for homes is a drop in interest rates. I’ve written about this a lot lately so I won’t dwell on it here, but the housing market is artificially frozen by how much interest rates jumped in 2022-2023, so to thaw that out will take a decline in rates. I expect when that happens, the pent-up demand to sell among existing homeowners will burst like a dam. If you believe that collective human behavior is basically predictable, you have had all these sales that were meant to have happened over the past few years but didn’t because people were artificially boxed in by the interest rate situation; eventually those sales will catch up. The pendulum swings. It may take some time but there is generally reversion to the mean. I see the housing crisis in both single-family homes and rental units easing in intensity for much of the rest of 2024. By 2025 and 2026 the environment will look and feel very different.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

Errors and Omissions and Further Considerations

Last week’s article about The College Crisis quickly became one of my most read and shared articles ever. Several readers asked/suggested/urged me to take a stronger stance on the situation unfolding at some of America’s top colleges, particularly since I am a Harvard alum. I agree. Here is my take: the performance of then-Harvard President Claudine Gay before Congress was extremely bad. She lacked the ability, clarity, or willingness to say clearly that Jewish students on campus should be protected from anti-Semitism. Subsequent concerns about plagiarism were most unfortunate indeed, but I found them to be credible. As an alum, it was frustrating to see the mental gymnastics taking place in some quarters to excuse her plagiarism when to me it seemed that if a student had done the same thing, he or she would have met serious consequences. It is unfortunate that Claudine Gay was the first black female president of Harvard and ended up having such an ignominious end, but the one-two punch of the Congressional testimony and the plagiarism were just too much.

An error: in that article I wrote:

According to data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve, total student loan balances nearly quadrupled from a level of $481 billion in 2006 to almost $18 billion in 2020.

The correct figure is that total student loan balances increased to $1.8 trillion. Oops.

Weekly Round-Up

Here are just a couple of things that caught my eye this week:

Per Lance Lambert of Parcl Labs, the median square footage of new homes built decreased by 3% last year, and in fact has been steadily decreasing for the last decade. Consumers are going slightly smaller in the fact of rising construction costs and higher interest rates. Read more here.

Planetizen shares data that there are over 55,000 office-to-residential conversations in the works. This is amidst dismal demand for traditional office space and robust demand for residentials. Read more here.

One Good Long Read

Thank you to everyone who reached out about last week’s long read about the Michigan couple that beat the lottery. People seemed to really like that story, as did I. Here is another one.

Eva Holland has a beautiful piece in Outside Magazine about the bus from the book and subsequent movie Into the Wild. The bus is where the featured subject, Chris McCandless, spent his last days. Even thought it was located in remote Alaska, the bus became a mecca for hikers seeking their own peace as well as a curiosity with a cult-like following. The problem is that some of these pilgrimages became dangerous and even deadly, so the bus was quietly removed by helicopter and placed in Alaska’s Museum of the North in Fairbanks, Alaska. From the piece:

Sure enough, a resident of the Healy area, Melanie Hall, had gone for a walk on Stampede Road—the paved portion of the historic overland trail that leads to where the bus sat for 60 years—when she spotted a helicopter with an enormous load. That looks like a bus, she thought as it flew closer, and moments later she knew: it was the bus. By the time Hall made it to a nearby gravel pit where the Chinook set the large vehicle down, another neighbor had arrived, and so had the borough mayor. As the bus was loaded onto a long trailer, Hall snapped photos she later posted on Facebook. A friend reposted them, and from there the pictures were shared and shared. The images went viral, and the state government began fielding media inquiries about the removal.

This is a story about a bus, but it is also about how inanimate objects with cultural significance can evoke wide ranges of emotions in people. There is also some great photography in the piece, which is also about what it means to restore a decaying item while still preserving its truth and authenticity. You can read this article by clicking here.

Have a great week, everybody!

Look forward to your weekly articles! What percentage of real estate loans are non recourse?

A very thorough and sensible analysis, Ben. Thanks for taking us back to GFC for important context. One additional piece of this narrative that has played out to a greater degree outside of Maine is the role of "professional" RE investors. When the GFC flushed out banks and builders as you described, unregulated funds seized an opportunity to buy developments in FL, AZ, NV and other hard hit areas. After flipping these properties for huge gains a few years later, these financial firms re-deployed their investors' funds across the country and became key determiners of rental rates. Their investment goals, horizons and practices differ greatly from traditional landlords - in many cases to the detriment to tenants, IMO. This is a big (and powerful) business now and may have changed the game for good in many places.