Recently here in Maine, there has been a spate of restaurant closings. The trend has hit both long-established businesses and upstarts alike. Patrons, workers, neighbors, and the business owners themselves, many of whom have put their life savings into the dream of owning a restaurant or bar, have been hit by a wave of heartache in an ever-changing restaurant scene. The overall economic landscape is challenging, for sure, but it is hitting restaurants particularly hard.

Communities feel the void when a restaurant closes, as it creates a vacant space on blocks that are often in need of vibrancy. The closure of a restaurant represents job losses, but also the loss of the ever-much needed “third space,” where people can come together in a place that is not their home or the workplace. When a restaurant closes, a little piece of the fabric that binds us all together is loosened.

Why are so many restaurants struggling right now? Just here in my area, there have been four stories in the Bangor Daily News within the last month about restaurants closing in Bangor, Searsport, Portland, and southern Maine, in general. This is not a problem that is local to Maine, however, or even the Northeast. Restaurants are closing all over the country.

It is also not a problem that is hitting only the local, mom-and-pop places, either. National chains like Applebees, TGI Fridays, and Dennys have all closed locations this year. Red Lobster is in bankruptcy. Outback Steakhouse is closing 41 stores across its multiple brands including Bonefish Grill and Carrabba’s Italian Grill. Subway has closed nearly 6,000 stores since 2015 and has seen net closures (i.e. more closures than openings) in each of the last eight years.

So what is happening? In many ways, other than during the pandemic, this is the hardest time in the last 40+ years to own a restaurant. And, as was told to me by one restaurant owner I spoke to this week in researching this topic, “In many ways, a lot of restaurants never actually recovered from the pandemic.”

Here are what I see as the variables currently at play:

Inflation

For a restaurant owner, the two biggest inputs are the price of ingredients and the price of labor. According to one estimate, these two things represent two-thirds of an overall restaurant budget.

Food inflation has been significant since 2020, driven by disruptions in global supply chains, rising fuel costs, and adverse weather conditions. Even the Russian invasion of Ukraine has hit food costs, as the country has historically been a large producer and worldwide exporter of grain. Between 2021 and 2023, food prices surged as much as 10-15% annually in some categories, particularly for meat, dairy, and grains. While many of the pandemic bottlenecks have eased up, prices did not necessarily come down in response.

For restaurants, this surge in food costs has been devastating. With razor-thin margins, many have had to raise menu prices, cut portion sizes, or substitute lower-quality ingredients to keep pace. Higher prices and compromises on the overall dining experience risk driving away customers, however, creating a balancing act for owners trying to maintain profitability. This is particularly challenging for smaller local restaurants. Although I noted above how the national chains have also been struggling, local restaurants are generally more burdened with the increasing cost of ingredients and supplies because they lack the leveraged purchasing power of large chains.

Labor Costs

Related to and interconnected with overall inflation, of course, is the rising cost of labor. According to the National Restaurant Association, labor costs have gone up 31% in the past four years. For an industry that typically makes about a 5% net profit margin on sales, an increase of 31% on one of the major inputs represents a shock to the income statement. The main ways around this are to cut staff or modify the experience (i.e. order from a counter rather than with a server, etc.), which risks undermining the customer experience, or to increase menu prices, which also risks driving customers away.

The labor shortage is particularly acute in certain parts of the country with a more limited workforce, including here in Maine. We have an older workforce, a low birthrate, and not much in-migration here in Maine (although migration has increased in recent years). With such a limited workforce, business owners of all types including restaurant owners have had to pay more and more to attract and retain workers. While rising wages are certainly good news for the worker, it provides a major impediment to the profitability (and therefore viability) of a lot of restaurants.

Other Costs

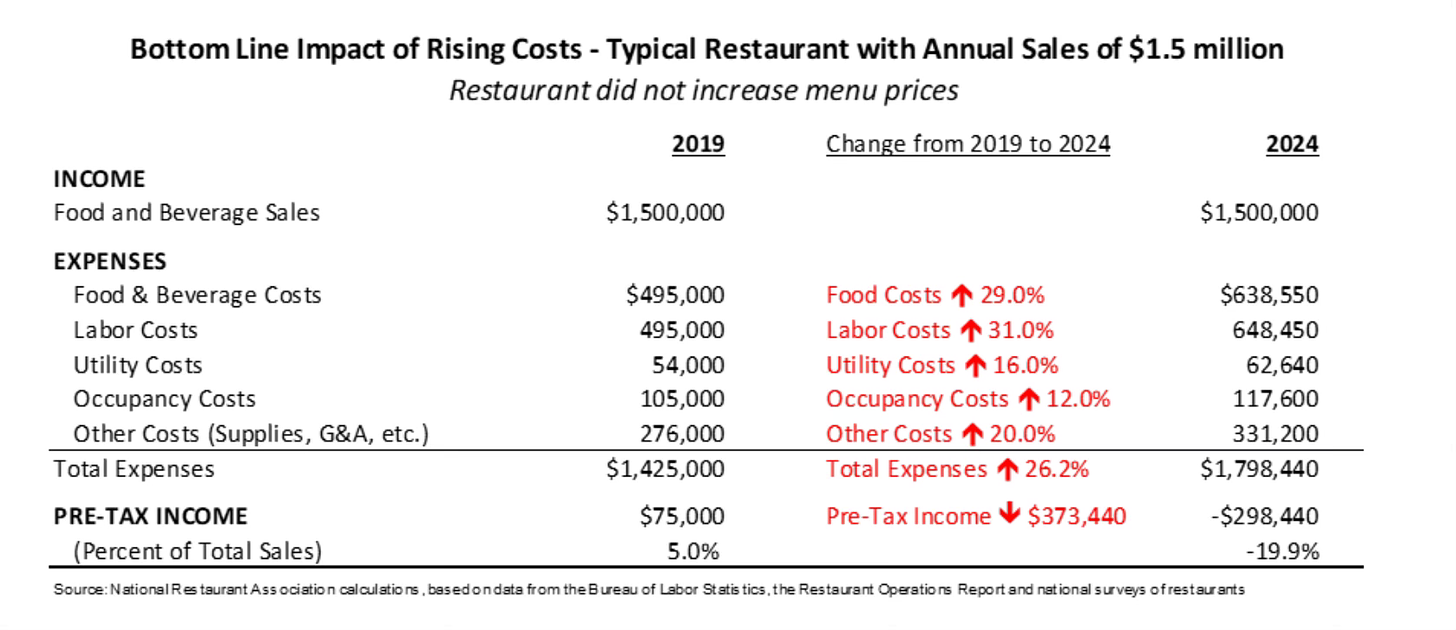

Rising costs are not just limited to food and labor, however. Insurance, property taxes, credit card processing fees, repairs and maintenance, the cost of marketing: you name it, it is all more expensive in 2024 than it was a year or two or five ago. The National Restaurant Association shared the calculations below showing the same gross sales of $1.5 million in 2019 and 2024, but with the rising costs of all other items included in the 2024 figures. Just operating the exact same business but with the updated costs takes the net bottom line from a pre-tax profit of $75,000 to a loss of nearly $300,000.

Evolving Competition

One additional variable at play is that the competitive landscape for restaurants is changing. Consumers have different expectations of what it means to eat out. This is cost-driven for sure, but it is also based on natural generational turnover. I will admit myself that our family sometimes gets takeout now because the cost of take-out is much cheaper than eating in the restaurant, especially when you are doing lower cost drinks at home. Since many of the mark-ups at a dine-in restaurant are on drinks and sides like chips and fries, it’s much more cost effective to just get the meal to-go and do the drinks at home (it’s also just exhausting to eat out with three kids who are picky eaters, if I’m being honest, and not worth the $100).

“Fast-casual” restaurants have also exploded in growth. These restaurants typically offer quicker service than full-service restaurants but maintain a higher focus on ingredient quality and dining atmosphere than traditional fast food spots like McDonald's or Taco Bell. Chipotle and Panera come to mind, for example, as examples of fast-growing, fast-casual dining. A lot of consumers of all ages, but I think particularly younger ones, want this experience more than they do the opportunity to sit in a more traditional restaurant with servers and table service. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that part of this is because younger people’s attention spans have shrunk with the rise of ubiquitous technology. Look around a Chipotle next time you’re there, for example. Practically everyone is sitting there on their phones, even people sitting across the table from one another. This is socially acceptable at a fast-casual spot, whereas at a more traditional dine-in restaurant it may still not be. Plus, lunch at Chipotle is probably, on average, $14 for someone dining solo, whereas it may be $25 at a more traditional lunch spot.

Pandemic Aid

One quick and final variable at play here, I think, that has led to a sudden jump in restaurant closures is that pandemic relief aid has finally run its course. There was actually quite a lot of pandemic aid for restaurant owners and business owners of all types including PPP loans, SBA EIDL loans, Employee Retention Credits, and sometimes further restaurant-specific aid at the local or state level depending on jurisdiction. All of that aid masked some of the problems the restaurant industry was experiencing due to inflation and generational turnover. The aid may have been just enough to get a lot of business owners through, but now that it has run out, there is a realization that the cavalry is not coming any longer. Some restaurants have just had to close, or may be about to, because the lifeline of pandemic aid has now run out.

Final Thoughts

Customers, too, are dealing with inflation in their own lives, and a discretionary purchase like going out to dinner is going to be easier for people to cut than, say, their mortgage, rent, or auto insurance. This is especially true as the price of dining out increases. Restaurants therefore find themselves fighting a negative spiral of needing to increase costs to meet expenses, but by doing so they push away the very people they need to come buy the product, which in this case is not only the meal itself but also the overall dining-out experience.

It is easy as a consumer to get frustrated by how much it costs to eat out. We all get sticker shock when the burger that used to cost $11 now costs $17 (and in some parts of the country, more like $25). It’s easy to blame the restaurant owner or to suspect them of greed or price gouging. But this is not actually what is happening. If restaurants are to remain profitable enough to keep the doors open, they have to make up the rising costs somewhere. Sometimes they can cut expenses here and there to help limit the blow, but unfortunately for all of us including both the consumer and the restaurant owner, a good portion of the rising costs have to get passed along to the consumer as there is often no other way to keep the doors open otherwise, and this means rising prices.

Is there hope for restaurants? Well, prices rarely tend to come down, but perhaps as overall inflation continues to level off particularly with regard to the cost of food ingredients, things will be better for restaurants. Otherwise, it will take the passage of time for consumers to simply accept that the burger now costs $17. People’s views on these sorts of things are pretty sticky, but eventually acquiescence takes hold, for better or worse, and that will probably be the case for people eating out.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

I didn’t quite have time for the Weekly Round-Up this week. We had a soccer tournament in Falmouth, Maine, I spent a day at a self-storage convention in Portland, followed by a school Halloween party, a speaking role at the Maine Chinese Conference, another Halloween party at the Maine Discovery Museum here in Bangor, followed by attending a wild 6-5 Maine Hockey overtime win against Quinnipiac on Saturday night. It’s been a great week, but a busy one, and one in which I didn’t have a lot of time for research and writing. We’ll see you next week!

Spot on! Also, what will fill the gap? In our family we have decided to build a third space to gather: a practical garage but with convertible hobby, movie, grilling stations. Taking all the eat out monies from 4 extensions of family (plus neighbors) to build savings and equity instead, all while fulfilling that need for community/social interaction. Perhaps now is a good time for a revival of clubs (elks, legions, odd fellows, etc.) as well as volunteering and use of community space: libraries, community centers, etc.

Well said, a balancing act to make a profit and still maintain quality